From the Grand Paris Express in the French capital to the Cityringen metro line in Copenhagen, Europe gives the impression to be forging ahead with big infrastructure projects that will help its cities develop in a sustainable way. The latest activity on this front is seen boosting the construction sector’s turnover from 1.9% in 2019 to 2% in 2020, according to Statista, a website that agglomerates official statistics.

But the investments being made across the continent have yet to reach the levels seen elsewhere in the world, whether it be in Asia, the Middle East or North America. And they only cover parts of the continent.

Although the sector is responsible for 21.1 million jobs, a number that has grown in recent years, it is still 11.8% lower than where it was in 2008 when the global financial crisis erupted. Some countries, such as Italy, remain far behind in terms of investment and employment as it is still struggles to recover from the global financial crisis.

This drag on the rest of Europe is shown in the numbers. Between 2008 and 2015, workers between the ages of 25 and 49 came to represent less of the sector’s workforce, falling from 65.3% to 61.8% of the total, according to the European Construction Sector Observatory. As a result, workers between the ages of 50 and 64 came to make up 28% rather than 22.2% of the total. The same trend has been seen in the level of education among workers of the sector. On average, less than 30% of them have low-level skills. But that percentage rises in countries like Portugal (71.9%), Spain (54%) and Italy (51.3%). Italy has been struggling more than most.

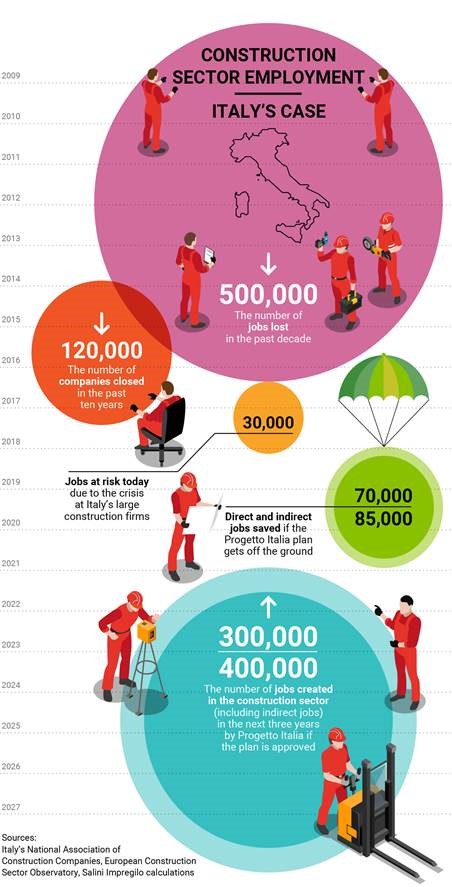

In the 10 years since the crisis erupted, the construction industry in the southern European country has lost about 500,000 jobs, according to the Associazione Nazionale Costruttori Edili (ANCE), or National Association of Builders.

Projects worth €36 billion remain blocked, even though €26 billion of the total have already been allocated by the Azienda Nazionale Autonoma delle Strade (ANAS), the state highway entity and Ferrovie dello Stato, the state railway operator.

When projects like the Turin-Lyon or Genoa-Milan high-speed rail lines are placed on hold, the jobs that they create also go on hold.

As a result, many of Italy’s construction companies are struggling, some on the verge of collapse.

In the last 10 years, 120,000 such companies have gone bankrupt. In recent months, five of the top 10 have started insolvency, or debt restructuring, procedures, putting about 30,000 jobs at risk.

A merger project to protect jobs

With Progetto Italia, or Project Italy, Salini Impregilo, the biggest builder in the country, plans to consolidate the sector, bringing together these struggling companies like Astaldi to create a single group. Financial institutions have shown interest in the plan, which would safeguard between 70,000 and 85,000 jobs. Should Progetto Italia succeed, it could help create another 350,000 jobs in the next five years as more projects get developed. The total impact on employment, directly and indirectly, could reach 500,000 jobs in as little as three years.

Infrastructure’s golden decade

According to the OECD, the ten years between 2008 and 2018 was a golden decade for major works, with annual growth rates often close to 4%.

In 2018 the turnover increased by 3.5%, while the growth forecast for 2019 is 3%. After a boom decade the sector will slow down slightly in the coming years, according to the OECD, especially in the United States where it will drop from 3% to 2.1% at the end of the current year.

However, Asian countries will continue to splash out on major works, with China in the lead, where the sector's turnover will still grow by 4% in 2019, confirming that Chinese megacities have no intention of stopping for breath.