The war in Ukraine and the subsequent EU race to find non-Russian sources of natural gas has reignited infrastructure-related discussions across Europe.

In particular, those discussions have been about ports and their ability to accommodate the large ships needed to transport liquid gas, followed by pipelines, which carry the gas from European ports to all EU member countries.

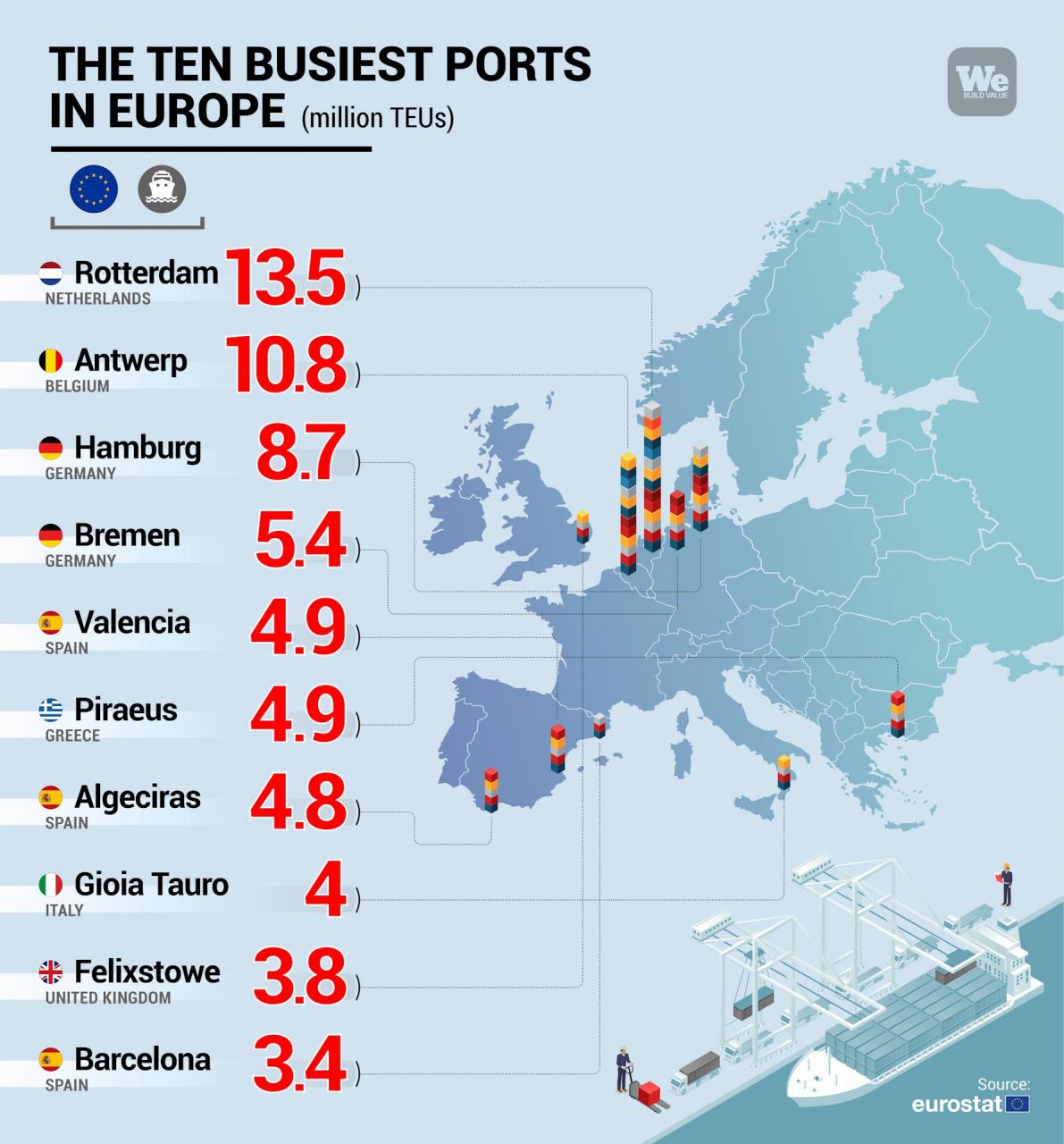

Currently, the port of Rotterdam, the largest port of call on the continent, has reached peak capacity for receiving and storing liquid natural gas. Speaking to the Financial Times, chief executive of the Rotterdam Port Authority Allard Castelein recently said,”Liquid natural gas (LNG) is a challenge. It will provide us with the most restrictions of all the goods we import. …You can’t build a (LNG) tank overnight.”

The issue raised in Rotterdam has “set sail” across the continent and “docked” in Spain. Unlike the Netherlands, Spain has six equipped terminals, more than is necessary for the amount of liquid gas being brought to the country’s shores. This is because there are not enough pipelines to transport the gas that would otherwise reach the coasts of France and other European countries. A plan to build the MIDCAT (Midi-Catalonia) pipeline has been at a standstill for years, and now it no longer seems feasible. The two operational pipelines that currently cross the Pyrenees can only transport one-tenth of Spain’s natural gas import capacity.

Tough alternatives to Russian gas

European heads of state are stepping up their institutional trips and seeking out alternative solutions to Russian gas, signing trade agreements primarily with Middle Eastern and North African countries. Given these constant efforts, eventually the new agreements should be able to cover 40% of the continent’s gas needs, the share currently covered by Russian suppliers.

Despite these agreements, the fundamental problem all European countries face is infrastructural inadequacy – the existing systems are not set up to receive and transport this precious resource.

Germany, one of the most Moscow-dependent countries, currently has no terminal equipped for liquid gas storage. As a temporary fix, the German government has chartered four large ships that can transform the gas from liquid to gaseous and use it for energy supply.

Meanwhile, the European Union is working on adopting new measures and investments to respond to the continent’s infrastructure shortcomings. Prime Minister of Portugal Antonio Costa previously spoke out about this issue at a March summit with Italy, Spain and Greece: “If we had built this infrastructure when there was the general agreement, which was in 2014, Europe would not now be in this situation of absolute dependence on Russia.”

Infrastructural inadequacies and the Turkish option

To date, almost all of Europe’s gas pipelines have been designed and built to work from East to West, to transport gas from Russia to EU countries. Despite numerous attempts made as early as 2009, and backed by the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas, Europe has failed to implement pipelines that can transport gas in the opposite direction, or, from the major Atlantic ports to the center and east of the continent.

Looking ahead, many have their sights set on Turkey, a NATO member country with the appropriate infrastructure to become a gas hub, securing imports to Southern Europe. A Greece-Bulgaria pipeline with gas supplied from Azerbaijan is expected to become operational next October. By the end of 2023, the Alexandroupolis terminal in northern Greece is expected to open, ensuring a connection with TAP, the mega-pipeline under construction (which will also reach Italy)

An independent and sustainable Europe

In light of what may happen in the coming months, and particularly in winter, when energy prices look set to rise due to the war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia, costs for new infrastructure are now more sustainable than ever.

Investing in the expansion of major ports as well as the creation of a comprehensive, efficient and sustainable pipeline network are now viable development strategies to ensure the European Union’s energy independence.

This all fits into the European plan to become a carbon-neutral continent by 2050. While this is an ambitious and difficult goal, particularly given the international crisis, it calls for a collective push for sustainability, from individual citizens to industrial policy.