Three years from now, Italy’s Autostrade del Sole, its main tollway artery, will celebrate its 60th anniversary. The first and most important section joining Milan and Naples was completed in 1964 after seven years of work and three months ahead of schedule.

Now almost 60 years later, those 755 kilometres (470 miles) of tollway, which immediately became the symbol of Italy’s post-war boom, are part of one of Europe’s most extensive road networks.

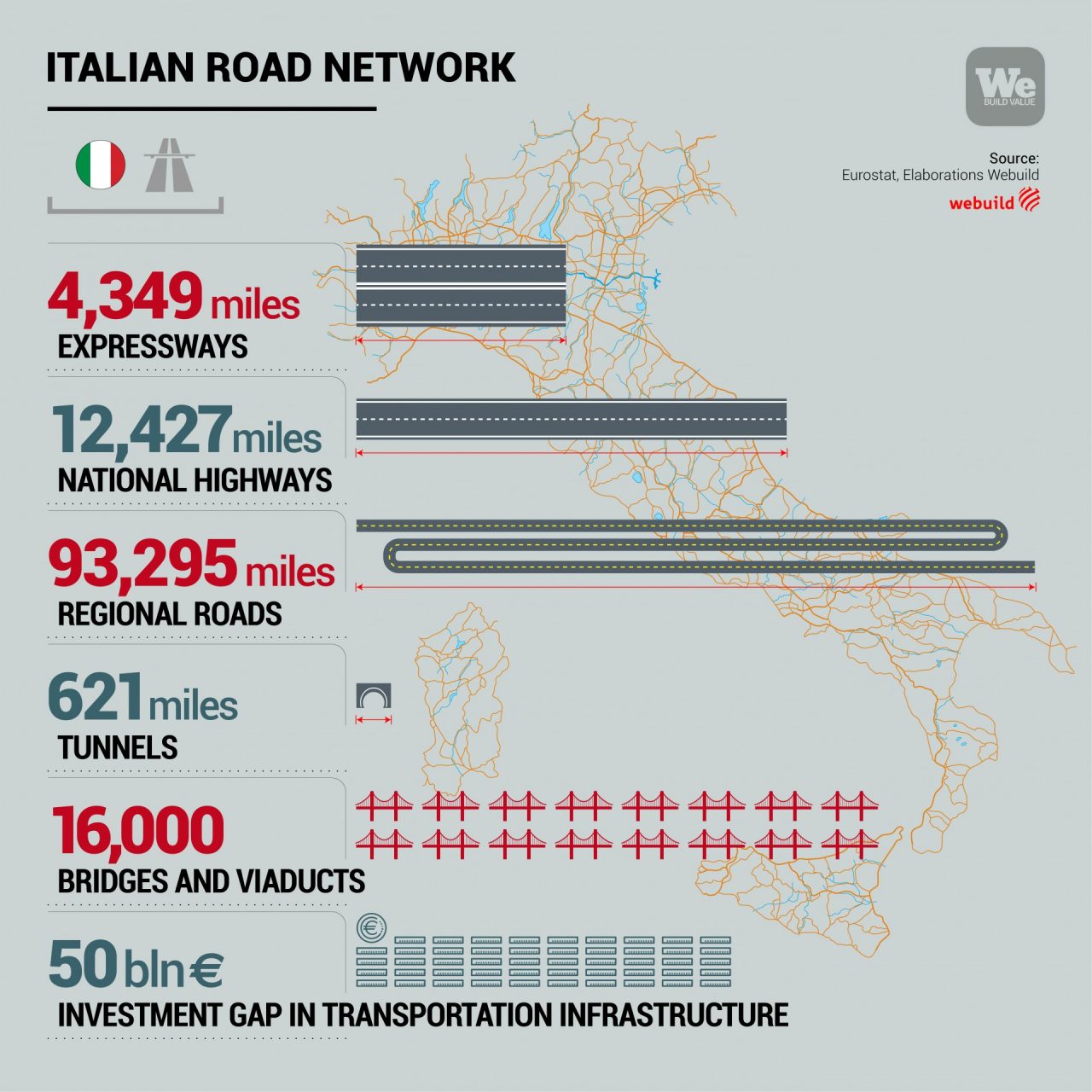

Seven thousand kilometres (4,349 miles) of expressways, 20,000 kilometres /12,427 miles) of national highways and 150,000 kilometres (93,295 miles) of regional roads, with over 1,000 kilometres (621 miles) of tunnels and 16,000 bridges and viaducts.

This heritage must be protected and safeguarded in the name of two principles: safety and efficiency. The collapse of Genoa’s Morandi bridge in August 2018, and the race to rebuild it with the San Giorgio Bridge, is still a constant reminder of the necessary importance of the maintenance of roads and bridges.

And it is precisely the modernisation of the Italian infrastructure network that is one of the main challenges facing the country after it completes its Covid-19 vaccine program and begins its social and economic recovery.

Today, Italy, along with other European Union countries in the process of drawing up the Recovery Plan, is looking to infrastructure maintenance as a key avenue to development. This development will be twofold in its purpose: taking a sustainable approach to infrastructure modernisation and creating jobs.

In the public transport system and upgrading of urban infrastructures alone, Italy needs to invest €50 billion ($59 billion) in maintenance. This capital could come, in part, through the Recovery Fund.

Roads: the lintel of Italian transport

Most of the necessary spending involves upgrading and modernising Italy’s road and rail network. In Italy today, 80% of goods and 80% of passengers still travel by road, not by rail.

Currently, each year between €3-4 billion ($3.5-4.7 billion) are spent on upgrades and extraordinary maintenance and another €3-4 billion on ordinary maintenance.

These investments are not enough to upgrade the existing road network, both in terms of safety and capacity, to better serve the population.

Between 2020 and 2021 many of the leading players in the sector such as the National Association of Builders (ANCE) have called for an increase in investment. Other leading players have announced new investments, like ASPI (one of the main private tollways operators) with €5.4 billion ($6.4 billion) in the next three years. ANAS, the state-owned highways manger, has announced it plans to call a total of €28 billion ($32 billion) in tenders by 2022.

Looking specifically at its expressways, Italy has a higher-than-European average number (22 kilometres of expressways every 1,000 square kilometres /13.7 miles per 386 square miles), a figure higher than the European average. Maintenance is the key problem. This is an issue that was thrust back in the spotlight after the August 2018 collapse of the Morandi bridge in Genoa, which helped accelerate maintenance work on many viaducts and road sections from northern to southern Italy.

Bridges without an owner

Italy is a country of mountains and hills, and bridges, for road infrastructure, are an essential tool. There are about 16,000 bridges in the country, most of them over 50 years old.

For this reason, almost 5,000 of these bridges must be monitored every year to check their state of health and, above all, if safety criteria are being followed. This is a complex and costly activity, but it is vital to maintain an asset base that, in many areas, should be renovated and in some cases even rebuilt.

It’s not always clear who is in charge. This issue emerged clearly in 2016 when the Annone overpass collapsed, causing a fatality. It emerged that the overpass had not been maintained because it was unclear which local authority knew had jurisdiction over it. In fact, in Italy there are almost 1,000 bridges whose control is parcelled out among provinces, municipalities or consortia.

Given the difficulty of verifying the ownership of these infrastructures, the Ministry of Transport asked ANAS to carry out a review of roads and these bridges.

Fragmented tenders and the need for better planning

To date, one of the biggest efficiency-inhibiting problems in infrastructure maintenance policies is Italy’s fragmented approach to tenders. Of tenders issued in Italy, 70% in this sector are valued at less than €10 million ($11.8 billion). In 50% of cases, tenders are generally awarded more than 12 months after their publication, a process that slowed even further during the first months of the pandemic.

In the first half of 2020, many road and highway maintenance tenders were not launched, indicating that the recovery in the infrastructure sector has yet to begin.

The rehabilitation of Italian infrastructure through a far-reaching maintenance plan for existing infrastructure is part of the Webuild Group’s commitment in Italy. Exactly one year ago, in April 2020, just a few weeks after the outbreak of the pandemic, Webuild CEO Pietro Salini presented a proposal for Italian infrastructure maintenance. This issue is a priority for safety reasons, but is also notable for what it can mean for job creation and the small and medium-sized companies affected by the Covid crisis.