Only a few months after inaugurating one of the biggest suspension bridges in the world, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has confirmed plans for a canal alongside the Bosphorus River, the latest ambitious project that underlines his ambitions to affirm the country’s economic heft.

«God willing, we will lay the foundation for a new canal parallel to the Bosphorus, what we call the Istanbul Canal – my dream – most likely at the endof this year or at the beginning of 2018», he told a forum in Belgrade on October 10.

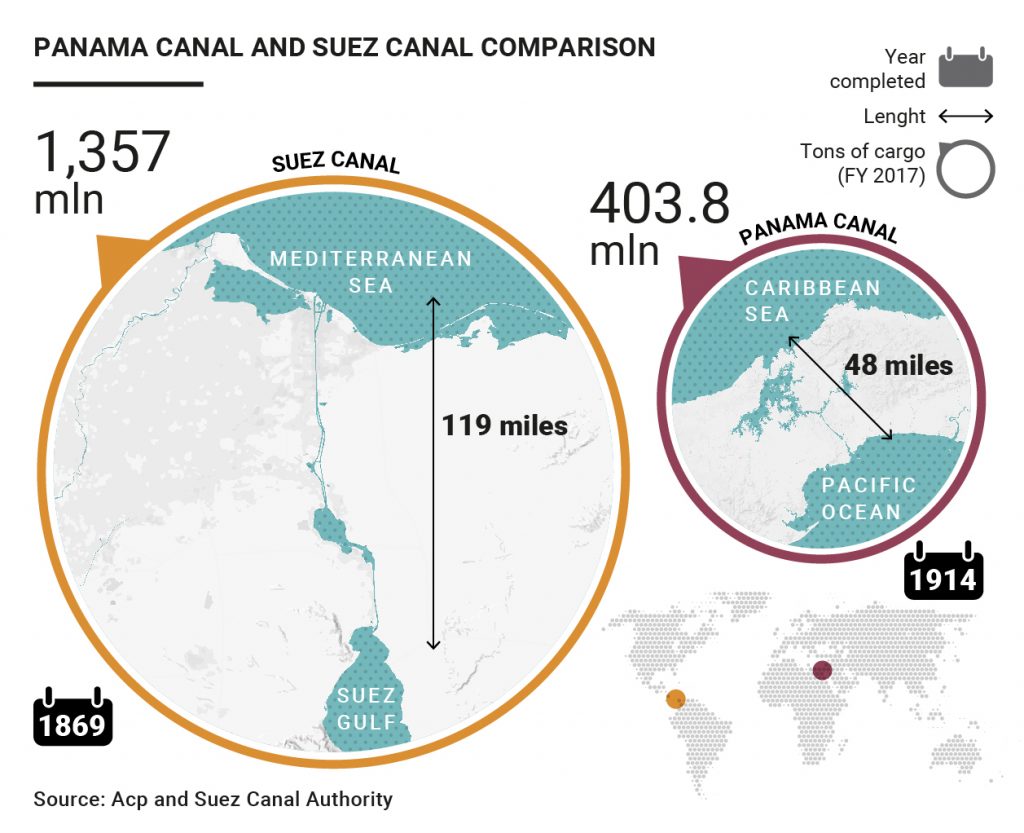

Although he had spoken about it in the past, Erdoğan’s announcement was an official endorsement for what would be the construction of one of the biggest and most complex infrastructure projects in the world. «There is a Suez, a Panama and there will be an Istanbul Canal», he said, referring to the two most renown canals in maritime trade.

It had only been a few weeks earlier that the construction of a canal running parallel to the Bosphorus seemed a difficult promise to keep. Although it had been mentioned several times as part of Erdoğan’s Vision 2023 plan (read more about investments in Turkey), few details about the canal had been given. The Vision concerns the investment of $400 billion in every sort of infrastructure ahead of the 100th anniversary of the foundation of the Turkish republic as Erdoğan seeks to rank the country among the top 10 economies in the world.

The latest of this series of megaprojects was the hybrid cable-stayed Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge, opened in August 2016. The widest suspension bridge in the world, it is the third to stretch across the Bosphorus near Istanbul.

The first time Erdoğan spoke of the canal was in 2011 during his election campaign for a third time in office. The idea had remained an idea until April 2016 when he announced it in a more emphatic way. «Canal Istanbul will be built. Regardless of what anyone says, we will build it», he vowed.

Near the end of the year, he had become more specific. «We will put out a tender for the project in 2017».

Transport Minister Ahmet Arslan has since given a few details: the canal will be 43 kilometres long and 25 metres deep; its width will range between 150 and 400 metres; and it will link the Black Sea with the Mediterranean on Istanbul’s European coast.

The actual course it will take has yet to be specified but the government has acknowledged that it would run near a $14 billion airport being built near Istanbul. Bridges and artificial islands would dot the canal.

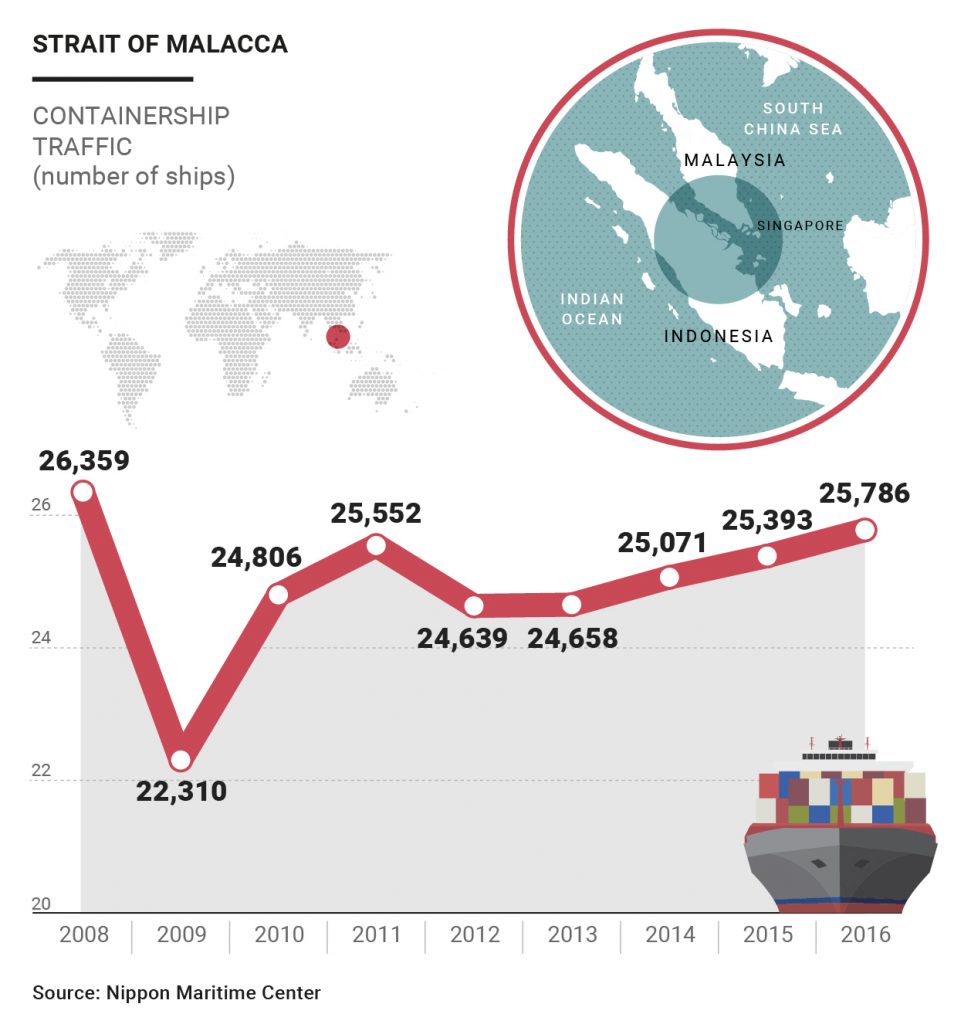

The reason for the canal is to relieve the Bosphorus of overwhelming shipping traffic, with some 53,000 boats using it every year.

The canal would act as a watery highway, encouraging more international trade to pass through Turkey and competing with the world’s other canals.

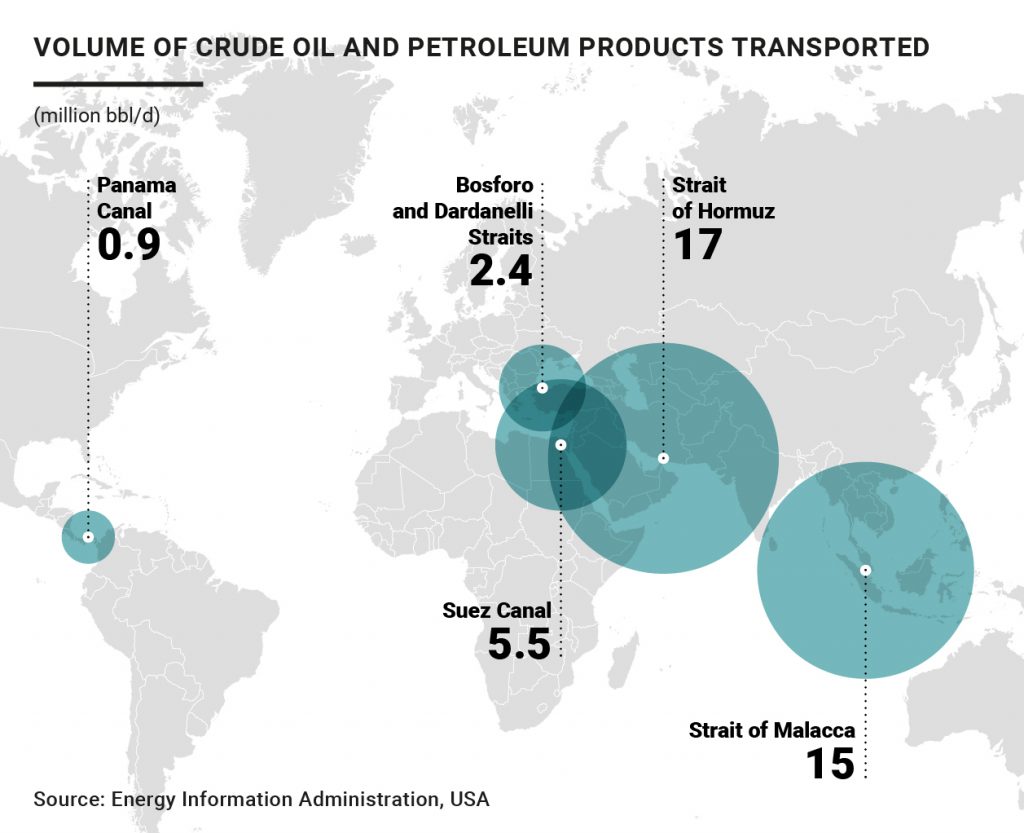

Every day, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, a government statistics office, 2.4 million barrels of oil is shipped through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles. The volume is less than the 5.5 million barrels that go through the Suez Canal but they are more than the 900,000 that cross the Panama Canal. In the last few years, commercial traffic along the Bosphorus has risen thanks to growing oil production in the fields of the Caspian Sea, which are linked to ports on the Black Sea. Natural gas from Russia and the Ukraine is also contributing to transforming the Black Sea into a strategic energy hub (where 7.3% of maritime traffic of the European Union).

In Istanbul, Europe’s largest city with nearly 15 million residents, the idea of a canal has been subject of debate for years because it dates back to 1999 when Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit included it among his various promises while on the campaign trail.

But it is its feasibility that counts. The government estimates the cost of building the canal at $10 billion, a number that foreign observers expect to rise. Its cost would nevertheless be more than the $5 billion spent on Panama’s new canal, built by an international consortium led by Salini Impregilo. It would likely top the $10 billion invested by Egypt to widen the Suez Canal. To raise the funds for the project, the local press has spoken of the likelihood that the government would ask for help from the Turkey Wealth Fund, the sovereign investment vehicle created in 2016 to financing large infrastructure projects.