During a trip to New York, Arturo Toscanini had insisted to Friedelind Wagner to put away a news article, saying he considered it bad taste to read about oneself. He did not want to know what Wagner was trying to show him: the growing curiosity on behalf of the public in their departure from Buenos Aires after it was delayed due to bad weather.

Despite his words, as recounted by biographer Harvey Sachs, Toscanini was most definitely interested in what was written about him. He kept himself informed of the latest articles – despite his denials.

The attention received by this famous orchestra conductor, whose interpretation of music set him at the same level as the great composers, made him one of the first pop stars of the modern age. Although he was difficult and demanding - rejecting interview requests and remaining suspicious of new recording technology because of what he felt was the distortion that it made of sound - Toscanini nurtured his public persona, ensuring that he remained a constant presence in the media.

Since as early as the 1920s, he made many studio recordings and conducted dozens of concerts on short- and long-wave radio with the orchestra that NBC had set up for him in New York in recognition not only of his talent but his marketing potential. He was one of the first conductors to have a concert broadcast on television in the United States. Magazines like “Time” and “Life” placed him on their covers on numerous occasions.

His goodbye concert with the New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra at Carnegie Hall in New York on April 29, 1936 was a media event without precedent. Tickets were sold out the first day they went on sale. “The New York Times” said 5,000 people came to the hall on the morning of the concert in a desperate bid to find tickets.

Toscanini kept being followed by the media like a star. During his time at the NBC Symphony Orchestra, which he conducted until 1954, its music reached millions of listeners thanks to the radio, a marriage made possible thanks to David Sarnoff, the head of RCA. The orchestra’s first performance to be broadcast on the radio was the night of Christmas in 1937 with 50,000 requests from people who wanted to follow the performance live at NBC’s studio.

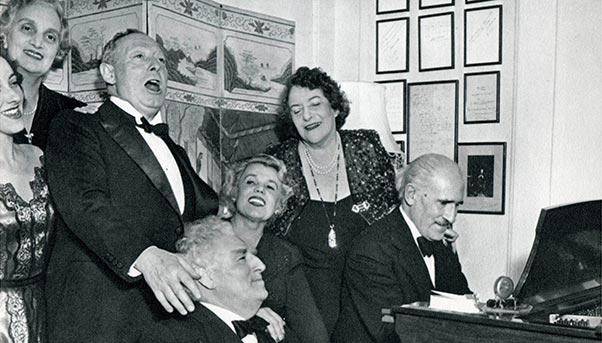

Private collection

Everything was possible as long as it went according to his rules. Legendary were his rejection of recordings: entire sides of records were to be made again, with orchestra members and technicians called back to the studio. The cost of the Maestro’s perfectionism terrorized music labels like Victor because he was never wholly satisfied with the latest recording technology. Despite his concern with the fidelity of the recording, the marvelous music can still be heard, the unique sound of the conductor who – together with Mahler – left his mark on how a composition was to be performed.

Toscanini also remained steadfast in the face of Hollywood, rejecting offers worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. He eventually accepted to appear in a short U.S. propaganda film during the war, leading an orchestra through compositions by Verdi such as “Forza del Destino” and “Inno delle Nazioni”. He would also add the “International” in recognition of the Socialist and Communist movements throughout the world alongside the U.S. national anthem.