In Argentina’s Veinticinco de Mayo department, in the middle of the Patagonian meseta, there is a small town named after Guido Jacobacci, an Italian engineer from Modena.

Surrounded by arid vegetation, afflicted by a cold climate and with economic activity supported almost exclusively by farms and tourism, Ingeniero Jacobacci is famous all over the world for being the ending point for La Trochita, or the Old Patagonian Express, the legendary train line built by the Italian engineer.

The historic Old Patagonian Express still crosses the steppe covered by low bushes populated by Patagonian sheep, foxes and hares. In 1999 the train was proclaimed a National Historic Monument by the Argentine government.

Guido Jacobacci did not design the narrow-gauge train with the intention of it becoming a symbol of adventure and tourist attraction; his goal was to build a transport infrastructure useful to support the development of the most extreme and backward areas of South America.

The origins of the Old Patagonian Express train

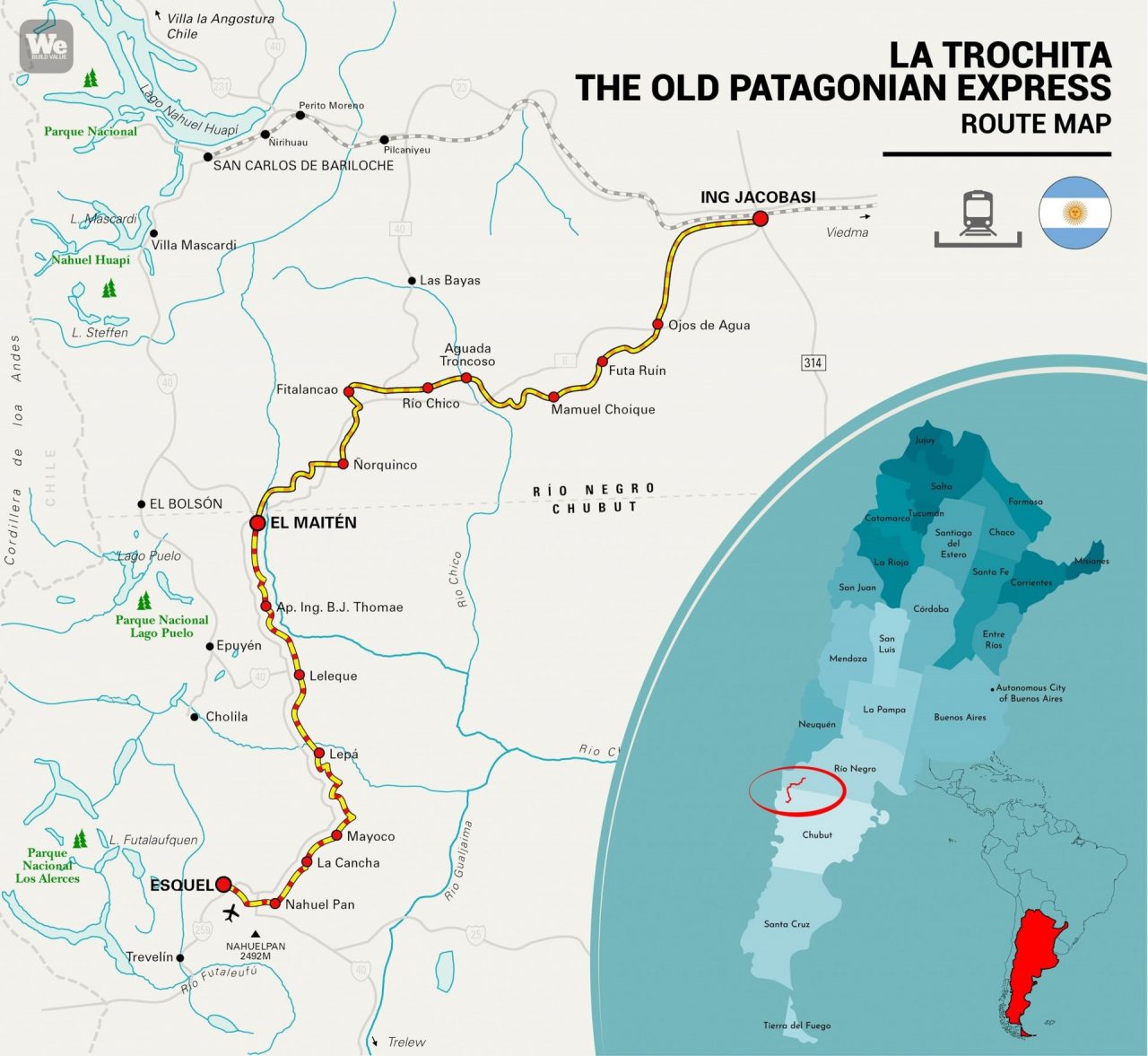

The Trochita is owned by the Argentine Southern Land Company, and was initially created as a freight transport infrastructure. Foodstuffs, but also skins, animals and wool from Patagonia ran along a 402-kilometre (249-mile) route from the city of Esquel to the terminus of Ingeniero Jacobacci.

The trains date back to 1922, although the tracks were not completed until 1945. Six trains ran along its tracks every day, passing through about one hundred towns.

In fact, initially the route connecting the provinces of Rio Negro and Chubut was planned to be much bigger. In 1908 the Argentine government wanted a railway line that crossed the entire territory of Patagonia, passing from the Andes to the ports on the south coast and arriving in Buenos Aires.

In reality, after World War I and its damage to the country’s economy, the project was put aside while work continued on the construction of the line connecting Esquel with Ingeniero Jacobacci – the Old Patagonian Express.

Over a thousand workers — most of them coming from the most remote areas of the world – built the line, and many of them settled down in Patagonia when construction finished. The construction site is complex, not least because the project required building a 105-metre-long (344-foot) bridge over the Chuco River and a 110-metre-long (360-foot) tunnel. The bridge and tunnel were necessary for the design, which, for the first time in history, connected regions otherwise isolated from the rest of the country.

When roads started to be built in the 1970s, the Old Patagonian Express saw its role as a strategic infrastructure for trade start to wane. But it slowly started a new life as an international tourist attraction thanks also in part to Paul Theroux’s book “The Old Patagonian Express.”

Despite the general interest and the arrival of mass tourism in the region, the line was not profitable enough to keep running. In 1992, it was decided to stop the trains once and for all. But the decision was met with national and international protests. Regional governments of the territories concerned decided to support the train exclusively with public funds, making sure it keeps running today.

Traveling through Patagonia

The wagons are made of wood, Spartan but warm. Inside each one, the air is heated by a cast iron wood-burning stove that was also used for light cooking and is now fed by travelers themselves. A teapot for tea and mate boils continuously on the stove.

Feeding the stove is the only way to stay warm in the polar cold that lasts for almost the entire year. And that’s enough to make the long journey 600 metres (1968 feet) above sea level through plateaus, lakes, forests and semi-desert areas. It is a journey through a world that seems motionless, on a train that never runs faster than 60 kilometers per hour (37 mph). A journey between history and legend, which for decades — before it became a major tourist attraction — marked the life and mystery of one of the world’s most unique regions.

Patagonia is the place where the famous outlaws Butch Cassidy and Sundance Kid fled U.S. marshals, and according to legend they are buried along the route of the Old Patagonia Express. The pair were not the only outlaws attracted to Patagonia. The men guarding the Baldwin locomotive that towed the train for years were forced to protect it from being robbed by Juan Batista Bairoletto, known in these regions as the Robin Hood of the Pampas.

The times of Butch Cassidy and Juan Batista Bairoletto are gone, and live on in the stories of the locals and history books. And the race towards the South has ended too, which was fueled by the dream of a Pan-American highway connecting this unspoiled territory with the rest of the continent. However, a work of human ingenuity has survived: locomotives, wagons, and tracks: all tools to tame an otherwise indominable nature.