America rediscovers its “rural” roots. Getting away from traffic, living in larger spaces, embracing entrepreneurial opportunities or taking advantage of a lower cost of living is a now widespread goal. The pandemic has made this trend even more pronounced, reversing the previous flight away from the countryside to the cities. In the past two years, according to a World Economic Forum study, 5 million Americans have left cities and moved to rural areas, compared with 3 million who have taken the opposite route.

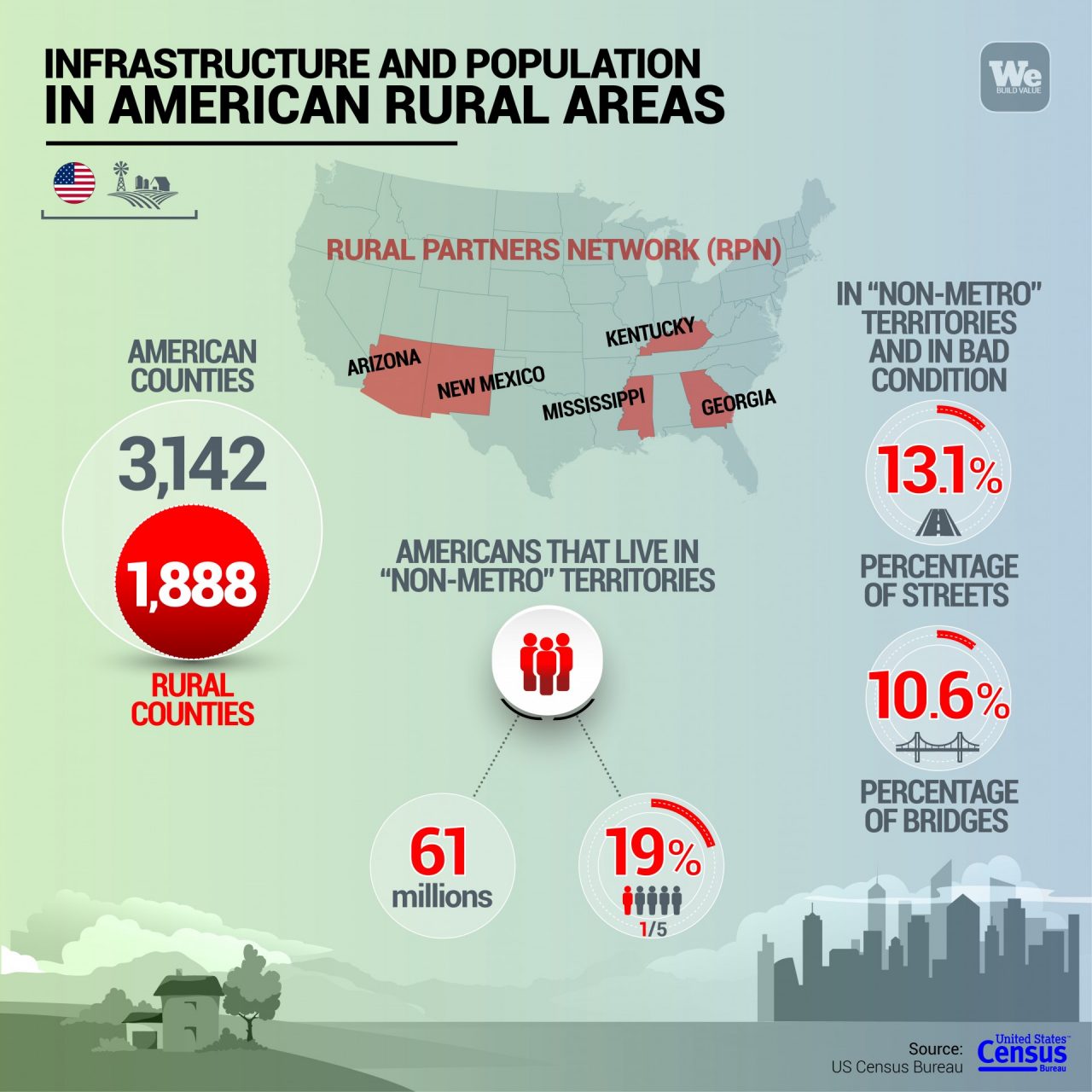

Today, out of 3,142 counties scattered from one end of the United States to the other, about 1,900 have a population that is more than half considered “rural” (as defined by the Census Bureau.) This flow of new residents into the countryside will eventually change the way these isolated communities are seen. Today the Census Bureau calls them simply “Everything Else.” Urban areas are defined as having at least 50,000 inhabitants, with high population density, nearby services, and adequate mobility. Everything else, precisely, is considered a rural area.

That “Everything Else” now counts 61 million inhabitants, 19% of the population, or about one out of five Americans. These are numbers that should not be underestimated, even less so in electoral terms. Agencies and organizations of both major parties are hoping to ride the wave of rural America’s desire for economic recovery, which has been penalised in recent decades by a lack of economic development and scarce resources for roads, airports, electrical networks, water systems, and the Internet.

The federal government’s latest projects aim to spark economic recovery by investing in infrastructure in far-flung areas outside urban centers. The trend began with the Trump administration’s “America First” programme and continues under President Joe Biden. The Biden administration has just launched the Rural Partners Network (RPN), a 25-person task force aimed at changing the way federal agencies interact with rural communities.

The new network will begin its work in 25 zones, comprising rural areas and Native American-run territories across Arizona, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and New Mexico. It will then expand to other states – a start, but it will take a while to make a dent, considering that the U.S. has 3,142 counties. In around 1,900 of these counties, more than half of each area’s population lives in rural conditions, according to the Census Bureau. The recent order signed by Biden to use steel, iron, and materials uniquely made in the U.S. is intended to improve living standards and access to jobs for these communities.

Transformation of rural areas starts with transport

Over the last 100 years, the U.S. population has tripled, going from 100 million in 1910 –– when rural populations were 54.4% –– to the current 331 million. This has rerouted labor and income to the cities, where there are more qualified workers for new manufacturing and high-tech industries. Now, the federal government has directed its departments to distribute federal funds from the Job Act and other budget bills with rural priorities in mind.

The Department of Transportation (DOT) has immediately made it clear, through an informational outline on the government agency’s website, that it will focus specifically on rural mobility, since rural communities “have faced decades of disinvestment.”

The document specifies that “13% of rural roads, and about 11% of off-system bridges—most of which are in rural areas—are in poor condition. Additionally, while 19% of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, 45% of all roadway fatalities occur on rural roads, two times higher than on urban roads.”

A bipartisan law to help revive rural areas

A bipartisan infrastructure law (abbreviated as BIL) will help rural communities meet these challenges by repairing roads and bridges, improving transportation options, and enhancing airports and ports to ensure that people and goods can move safely and efficiently. “The BIL will rebuild and repair rural infrastructure, provide connectivity that will spur economic growth in rural communities, and create good-paying jobs in communities across the country,” the DOT confirms.

Responses to climate change will also play a significant role in the future of rural areas where energy production has long been the backbone of jobs, economies, and livelihoods, a backbone that has contributed significantly to American prosperity. Today, environmental protection and resulting market demand are driving a shift from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources. To create new investment opportunities in this transition, the Department of Agriculture (USDA) is setting up funds like the Rural Energy for America Program (REAP), through which small business owners can transition to clean energy, make energy efficiency improvements, and reduce operating costs.

To encourage take-up of these programs, the Department has begun to publish individual approved projects, spanning the entire country from east to west. The owners of Margo’s Pottery and Fine Crafts in Buffalo, a town of 4,600 souls in Wyoming, were awarded a grant to purchase and install a six-kilowatt solar panel on the roof of their pottery and crafts production house. In Los Ranchos de Albuquerque, a village in New Mexico, Matthew Draper’s farm, which produces eggs and vegetables for the surrounding community, was able to obtain the resources to switch to solar power, saving about $1,200 a year and covering its own energy needs. In Alaska, a farm that specializes in strawberry and blueberry production now runs entirely on solar panels.

From injecting micro-resources to major projects. For example, Alabama’s Medical West Hospital Authority will use $360 million in Community Facilities programme funding to build a state-of-the-art 200-bed hospital. Rural communities like these are receiving support for new infrastructure and are increasingly positioning themselves at the center of federal and state programmes to provide mobility, clean water, energy, and internet connections, or to repair damage caused by natural disasters.

In February 2021, for example, winter storm Uri exposed the fragility of Texas’ infrastructure, with an energy crisis that quickly turned into a water crisis. A highly predictable situation considering that the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) has long assigned a C- for drinking water and a D for wastewater networks in Texas, pointing out the poor planning for these structures, especially in rural areas. The focus is now increasingly directed at remote areas, so much so that $2.9 billion in funding will flow into Texas this year through the state agency Texas Water Development Board for water infrastructure improvements.