It says a lot about a company when the cook is the second highest paid worker on a construction site.

It shows it recognises the importance of keeping its workers well fed – given how the success of a project depends on them.

Codelfa-Cogefar, the Italian partnership known for having taken part in the construction of projects that helped develop cities if not countries this past century, is one such company.

Such was its respect for its workers that – in at least one case – it became a subject of study. And that case was its involvement in the construction of the Tongariro Power Scheme, one of New Zealand’s largest hydropower projects.

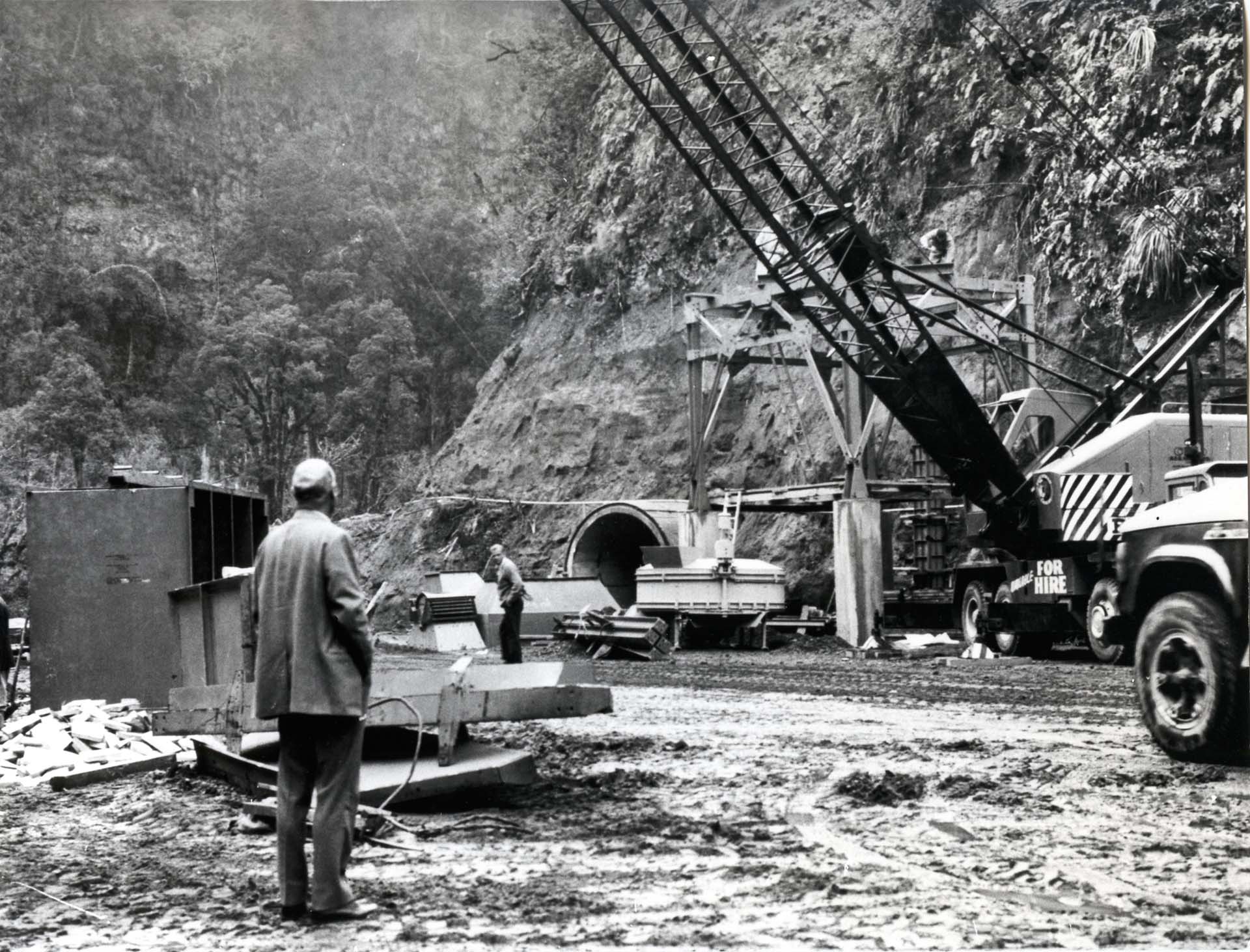

Tunnelling Expertise

After signing in 1967 the first of several contracts to excavate tens of kilometres of tunnels for the scheme, Codelfa-Cogefar got the government to let it bring not only its experts from Italy, but also their food and drink of choice. Given the circumstances, it did not have to do much convincing to have its unusual request accepted. The country did not have enough tunnellers of its own, and the government was in a hurry to build more power stations because a growing population had created the risk of blackouts. “New Zealand companies lacked…tunnelling expertise”, reads a 2001 article in The Waikato Times, a local newspaper. “That had to come from Italy”.

Imaginative Undertaking

Begun in 1964, the construction of Tongariro was as much an engineering feat as the Snowy Scheme in Australia. It would utilise water from 36 streams and rivers through nearly 80 kilometres of pipes, aqueducts and tunnels along the flanks of a volcanic mountain range in the North Island’s remote central plateau. The waters would then be channeled through three hydropower stations to generate electricity before emptying into a lake. “The power of rivers from more than a thousand square miles (2,600 square kilometres) of country will be harnessed and led for much of the way underground in one of New Zealand’s most imaginative engineering undertakings”, says the narrator of “Tongariro Power”, a 1970 documentary about the project.

Completed in 1983, Tongariro produces about 4 percent of New Zealand’s total electricity generation. Operated by utility Genesis Energy, its power stations include the 120-megawatt (MW) Rangipō, Tokaanu (240 MW) and Mangaio (1.8 MW). It produces an average of 1,300 gigawatt-hours (GWh) a year, enough for about 160,000 households.

Italian Legacy

Codelfa-Cogefar, a predecessor of Italian civil engineering group Webuild, was known in many parts of the world for its work on large, complex projects. Codelfa stood for Costruzioni del Favero SpA, while Cogefar was Costruzioni Generali Farsura SpA. In Australia, they would later do the tunnelling for the Melbourne Underground Rail Loop, and contribute to the construction of the Wivenhoe Power Scheme in the state of Queensland. Their legacy in Australia is being perpetuated by Webuild, which is currently developing Snowy 2.0, the largest renewable energy project in the country that will expand the Snowy Scheme.

Second Highest Paid

As Italians joined the hundreds of workers settling in camps on either side of the mountain range and in the nearby town of Tūrangi, Codelfa-Cogefar went about preparing to make them feel at home. Despite the import restrictions in place at the time, Codelfa-Cogefar brought food and wine in vast quantities, according to historian David Simcock in a 2020 academic paper published in the New Zealand Journal of History. Imports included pasta, olive oil and cheese. As if that was not enough, Codelfa-Cogefar also imported the cooks from Italy. Their importance to the project was evident in the wages they would earn. “Their pay rates…using 1975 rates, were $1.96 per hour, just one cent less than the most important person, the tunnel headman”, says Simcock.

Skill and Perseverance

Of the three tunnels excavated by Codelfa-Cogefar, the longest was the Moawhango-Tongariro on the eastern flank of the mountain range. At slightly more than 19 kilometres, it took the world record for a while as the longest driven as a single tunnel. Its length had obliged workers to excavate it from both ends and eventually meet in the middle. The fact that they were able to do it without the use of lasers, computers or satellite positioning systems demonstrated their engineering prowess. To this day, the Moawhango-Tongariro tunnel remains one of the longest hydro tunnels in the southern hemisphere.

This expertise also enabled the Italian tunnellers to overcome the difficult ground conditions they faced during their time on the project. They encountered unstable volcanic alluvium and enormous quantities of ground water that routinely poured into the tunnels. There were instances when rocks would fall from the ceiling if not the entire ceiling itself. “Sometimes, conditions are so bad that low pilot drives are pushed ahead first and progress slowed to a mere two or three hard-won feet a day”, says the documentary’s narrator. An old booklet by Codelfa-Cogefar also speaks of the challenges. “Due to the constantly variable conditions…machine excavation was discarded and conventional drill and shoot excavation was used throughout”, it says. “Mechanization was impractical (so)…the drilling cycle was carried out with four air driven, pusher-leg rock drills. The many faults and large inflows of water encountered in both headings demanded a high level of individual skill and perseverance from the tunnellers”.

No Lives Lost

Despite these seemingly insurmountable challenges, the tunnel was completed with no fatalities, an indication of how much the safety of its workers was just as important to Codelfa-Cogefar as their stomachs. “It is largely due to their experience and daily application that this tunnel can be remembered also as the one that frustrated the generally applied statistic of one fatality per mile: no lives were lost on the job throughout the duration”, the booklet proudly states.

In the end, Codelfa-Cogefar excavated more than 40 kilometres of tunnels and passages for the project – more than half of the total. Since the volcanic range – dominated by mounts Ruapehu, Tongariro and Ngauruhoe – remains active, Genesis has procedures in place to protect the public and the scheme. Detection of activity will trigger the automatic closure of intakes to make lahar, ash and lava pass over – and not through – the power scheme.