Riding the wave of economic benefits produced by the 2010 World Cup, South Africa is following the route of further investments to modernise the country and keep supporting its growth. In its plans to invest €17 billion during the next three years, infrastructure and transportation are key components.he plan foresees the purchase of 232 diesel locomotives for passenger trains and 100 for merchandise. At the centre of the plan remains the development of urban mobility in the most important centres of the country.

Cape Town is definitely one of them: it is the third most populous in South Africa after Johannesburg and Durban as well as the seat of parliament. For a number of years, the city has been at the heart of an ambitious plan to improve its infrastructure to reduce commuting times and improve the quality of life of its residents.

Bus Rapid Transport System

Lwandle is a bright young man with a toothy grin. We meet him on a Saturday afternoon waiting for his shift to start at the Omuramba Stationi, roughly 13 kilometres from Cape Town’s city centre.

He has been a bus driver for three-and-a-half years, one of 466 bus drivers employed in the City of Cape Town’s new Bus Rapid Transport (BRT) system. The BRT is the special network of lanes that the City launched in May 2010 to improve the quality of mobility for its residents.

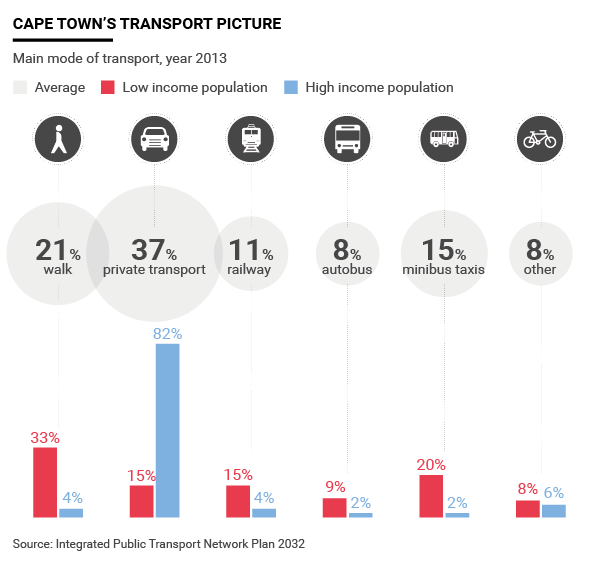

Launched to coincide with South Africa’s hosting of the FIFA World Cup, they marked a significant change in the way all Capetonians access the city. And, in a country where the previous regime’s Apartheid and Group Areas Acts meant that many communities were effectively cut off from the city, this improvement has had many social and economic benefits.

“Before the buses, it wasn’t the easiest thing to get to the city,” says Lwandle. “You could catch the train. Or the taxi. But many times the taxis didn’t go to where you wanted and people still had to walk a part of the way to their jobs. They can also be expensive.”

By taxis, Lwandle is referring to the minibus taxis, a largely informal network of operators (although many do belong to a taxi association) that arose as a solution to the transport problems South Africa’s past political situation created. “They also weren’t the safest,” he adds, “which meant sometimes people were scared to take them and didn’t pitch up for work.”

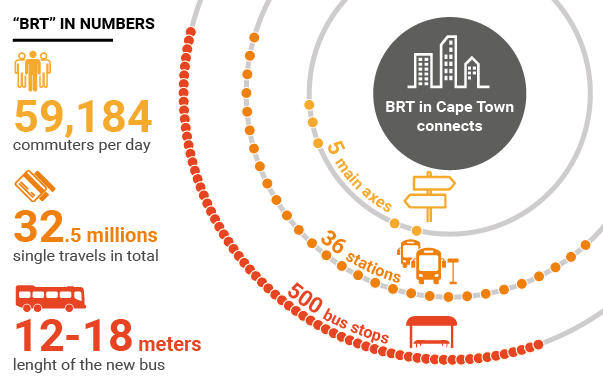

Easily recognised by their exclusive-use red concrete lanes, the building of the BRT has ushered in a new era of safe, affordable and decent commuting to and around the city. While it started with a direct route from the Civic Centre to Cape Town International Airport, resulting also in a widening of the N2 highway and construction of flyovers at interchanges entering the city, it now has five trunk routes, 36 stations and 500 bus stops. These modern stations and dedicated bus lanes have all been constructed from the ground up, while many of the bus stops have been retrofitted to existing roads.

The steady increase in the use of the buses has continued with townships like Khayeliltsha receiving 34 kilometres of new concrete bus lanes and 10 extra stops. This has paved the way for 12-metre and 18-metre-long, low-floor buses to help get people to their jobs and contributes to over 59,184 passenger journeys daily. In fact, 32.5 million passenger journeys have already been recorded since inception, an impact that’s been profoundly felt among local business.

Integrated Public Transport Plan

But the BRT is just one prong of the Integrated Public Transport Network Plan (IPTN). The bus lanes are envisioned to complement the commuter rail routes, many of which are already in existence. With the burgeoning city, new rail lines and upgrading of current lines is projected for the next 17 years in Cape Town.

In Kalk Bay and Clovelly, situated to the south of the city centre, an entire stretch of road and rail is currently being improved.

To the east of the city, nine kilometres of new connecting track is projected to make it far easier for residents from places like Mfuleni, Blue Downs and Wimbledon to access the city.

James, a nightshift security guard waiting at the bus stop outside the informal settlement of Imizamu Yethu in Hout Bay – southwest of Cape Town and on the other side of Table Mountain – says: “The only real problem I see is that the transport doesn’t always run on time. That makes it sometimes difficult for me because I can be late for work.”

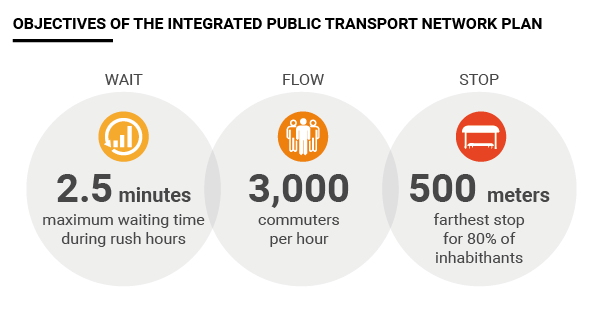

The IPTN operations plan to address this too. It’s striving to achieve a maximum of two-and-a-half minute waiting interval during peak times, accommodating 3,000 commuters per hour. “We plan to place 80% of residents within 500 metres of a trunk (BRT or rail) or bus feeder route,” enthuses Councillor Brett Herron, the Mayoral Committee Member for Transport.

A Solution for Pedestrians and Cyclists

Safe, well-lit walkways and cycle lanes are also an integral part of this plan. In Kraaifontein, a large new suburb in the northern parts of Cape Town, the city has spent over R35 million during the past six months just on the pedestrian and cycle paths. This is in addition to the R28.5 million already spent from 2014 to 2015 by the city on providing a safe walking route for Kraaifontein residents to their places of work in nearby Brackenfell, which houses industrial parks and businesses.

To date, the City of Cape Town has constructed approximately 450 kilometres of cycle lanes, which includes cycle lanes outside the road space and demarcated cycle facilities.

The BRT infrastructure has been developed with a view to expand the current fleet of diesel buses to 12-metre-long electric buses. By virtue of their design, these buses have more seating space and will, once implemented, also have charging infrastructure reliant only on solar power. This will make Cape Town the first city in Africa to use alternative energy buses, and will enable Transport Cape Town to earn carbon credits to sell on to developed countries.

The city also acknowledges that the minibus taxi industry is an entrenched part of South African culture and commuting. Stand on any street corner in South Africa and you’ll be hard-pressed not to see any minibus taxis pass by. However, these ranks are very often makeshift stops with little to no infrastructure. There’s no shelter or basic

facilities. As a way of addressing this with a view to the future, the city unveiled its first ‘Green’ Taxi Rank on August 25, 2014. Designed specifically to overcome the challenges of taxi commuting in a sustainable way, the rank at Wallacedene in Cape Town was built from the ground up at a cost of R25 million. It operates entirely off the grid, generating all its own electricity – in fact, since it was launched, it has only used one hour of electricity from the grid, which was needed for power tools in the final construction. Everything at the taxi rank is powered by a system of photovoltaic panels on its roofs and a battery storage system underground.

All this development has set the benchmark for future public transport facilities.

Modern Transport to Unite a Community

With the large natural impediments around Cape Town - like Table Bay, Table Mountain and False Bay – and the segregated planning of the Apartheid years, many communities were simply excluded from the city in the past. The infrastructural transport developments in Cape Town appear to be focused on the reconnection of communities and the sustainable mobility of its residents.

The impact this has had on people in Cape Town is palpable: they move freely and easily to and from their places of work and are able to enjoy all the city has to offer.

And with residents in outlying areas like Hout Bay and Atlantis, new townships like Dunoon and established townships like Khayelitsha showing the most impressive adoption rates of the City of Cape Town’s transport plans, it’s clear that access to and mobility within Cape Town is improving by the day. Something that Capetonians like Lwandle will be smiling about for many years to come.