The barges sail slowly down the East River as they glide past Manhattan’s famous skyline. They come from the Red Hook Container Terminal in Brooklyn, one of the city’s ports handling the huge amount of foodstuffs that will soon be headed for stores across the city. New York City’s enormous waterfront, to give just one example, moves 20 million bananas each week. These river barges are a huge helping hand for the city’s overloaded transport system, that – by exploiting these river transport assets – can reduce the number of trucks on New York’s streets each year by 30,000. The barges can navigate the sea, and the two large rivers, the Hudson and the East River, to transport goods into the city’s boroughs: Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, The Bronx and Manhattan. The 198 million tons of merchandise delivered in 2016 by 2045 will balloon to 312 million, according to the NYC Economic Development Corporation.

This explosive growth in the largest consumer market in the United States is an opportunity that Mayor Bill de Blasio intends to exploit by modernising the city’s water transport and improving its connection to the city’s railway network. Today 89% of New York’s freight is delivered through the city’s streets, at a huge cost to the metropolis in terms of traffic congestion. In 2017 this congestion cost the local economy an estimated $862 million (destined to rise to $1.1 billion by 2045), whereas investment in rail and water transport has stagnated for several years.

A new urban freight transport system

The situation risks becoming critical even in the next few years – something the city administration is well aware of and intends to remedy. That’s why Mayor de Blasio in July kicked off a new plan, called Freight NYC, spending $100 million in spending to relaunch maritime and rail transport.

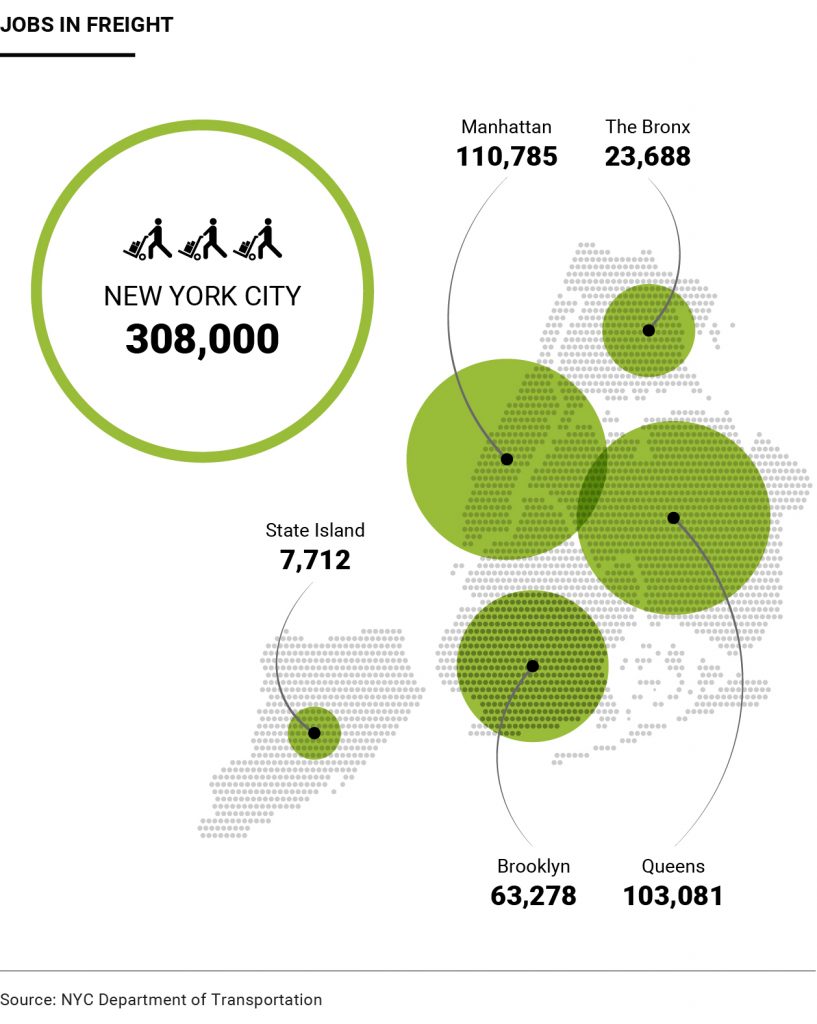

This investment, according to the NYC Department of Transportation, has four goals: to create 5,000 jobs in the next ten years; change the access routes to the city by moving the focus to intermodal maritime/rail links; modernise the port system; reduce pollution and encourage sustainable economic development.

The goals will be reached by investing in both water transport and rail links. Specifically, new connections will be built in Queens and in Brooklyn linking the national railway grid with shipping, which the NYC Economic Development Corporation estimates will cut truck trips in the city by 500,000.

The true strength of the project likes in the idea of integrating these two means of transport by creating intermodal hubs in all of New York’s five boroughs (Manhattan, Brooklyn, Staten Island, Queens, and the Bronx). According to the plan, two of the hubs will be in Queens, one in Brooklyn, two in Staten Island, one in the Bronx and one in Manhattan. Overall, these are pre-existing infrastructures that need to be upgraded and connected in an efficient manner to the rest of the transportation network. This task must be completed within the next ten years, before the city is suffocated by trucks.

Urgent investments for the city’s future

If the city does not re-think the way it manages its freight traffic, the risks to New York’s mobility are significant. The starting point is to improve the performance of the city’s far-flung logistics network: 90 miles of freight rail track, nine train stations, 1,300 miles of special truck routes, three maritime facilities and the enormous JFK International Airport. This wide range of options has up until now has been dominated by road transport, and the access points used by trucks are always the same: the George Washington Bridge, the Goethals Bridge, Lincoln Tunnel and the transport arteries that arrive from New Jersey.

These key infrastructure works will be joined by the new UnionPortBridge in the Bronx, another key entry point to Manhattan. The original bridge, built in 1953, is crossed by 55,000 vehicles each day, and has become obsolete. That’s why it will soon be replaced by a new bridge costing $232 million, built by Salini Impregilo’s U.S. unit Lane Construction.

Despite the city administration’s efforts, traffic congestion has become one of the city’s worst problems, with New York ranking just behind Los Angeles in terms of the second-highest amount of time residents spend behind the wheel of their car each year (89.4 hours in 2016). It is the trucks that make the streets impossible: in 2016, 14.5 million freight trucks entered the city, and 3.5 million made the trip out. This is an obstacle to New York City’s future business growth; a huge retail market growing year after year creating the need for a more modern and efficient logistics network. This new network is the one now envisioned by the city government, convinced that it will succeed in giving the Big Apple a new freight transport system.