The Trans-Iranian Railway is not only an example of nation-building but also one of engineering prowess.

A visionary project that took more than a decade to complete, it crosses Iran from north to south through some of the country’s most varied – and often treacherous – terrain.

Its builders faced malarial marshes, steep mountains, immense plateaux, deep valleys, scorching deserts and vast lowlands – conditions that tested the ingenuity, resource fulness – let alone resilience – of the best of them.

Stretching some 1,400 kilometres, it was the first railway to unite the country, a legacy of Reza Shah.

Although Iran, known as Persia at the time of his reign, already had a few hundred kilometres of railway lines in disparate parts of the country, they were insufficient to contribute to the modernization of this vast land. So the Shah had the first plans drafted in 1925 shortly after coming to power. Begun two years later, construction of the Trans-Iranian Railway took 11 years to complete. Its enormous cost was partly financed by taxes, such as those on tea and sugar imposted by the Shah.

The railway runs from the northern port of Bandar-e Shah on the Caspian Sea to the port of Bandar-e Shahpur on the Persian Gulf in the south. It has the capital, Tehran, at its hub. Other lines were to be built later in the century, extending from this main artery to reach other parts of the country. The enormous work to link the two coasts involved countless foreign contractors, including Impresit, one of Salin Impregilo’s early predecessors. Since no single contractor had the capability of accomplishing the task alone, the work was divided into sections, also known as lots. The Italian builder acquired five of the most challenging.

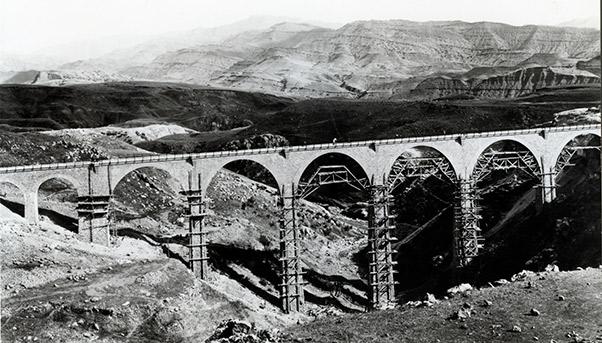

“The lots conferred to Impresit were among the most difficult to execute”, says Andrea Filippo Saba, a University of Florence researcher, in a 1995 academic paper. Four of the lots were in the north where Impresit had to build an access ramp to a tunnel under Gaduk Pass in the Alborz mountain range. It climbs 1,200 metres in less than 50 kilometres. With an average gradient of 26%, it rises from 1,000 metres above sea level to 2,200 metres. At one point, it zigzags three times up the side of a mountain. Another challenge was the construction of a bridge across a narrow valley to allow the train to exit a tunnel from the side of one mountain and enter another tunnel on the side of an adjacent mountain. In order to build the arch of the bridge 70 metres above the river valley, the builders had to erect two iron platforms supported by slats or meshes of fortified concrete. At another site along the side of a mountain, they had to set up makeshift cable cars in order to be able to import the sand required to make cement. Winters were merciless, sometimes dumping two metres of snow.

Impresit’s fifth lot was in the south, where the train was to wind its way through the mountainous province of Khuzestan. The remoteness of the location made it difficult to maintain supply lines. In summer, temperatures reached such scorching levels that work was conducted at night. Apart from the dozen engineers, 20 administrative officers and 80 technicians, there were 12,000 locals – all working uninterruptedly for 26 months.

In the end, Impresit built about 50 kilometres of railway, including 73 tunnels and 2,000 metres of bridges and viaducts.