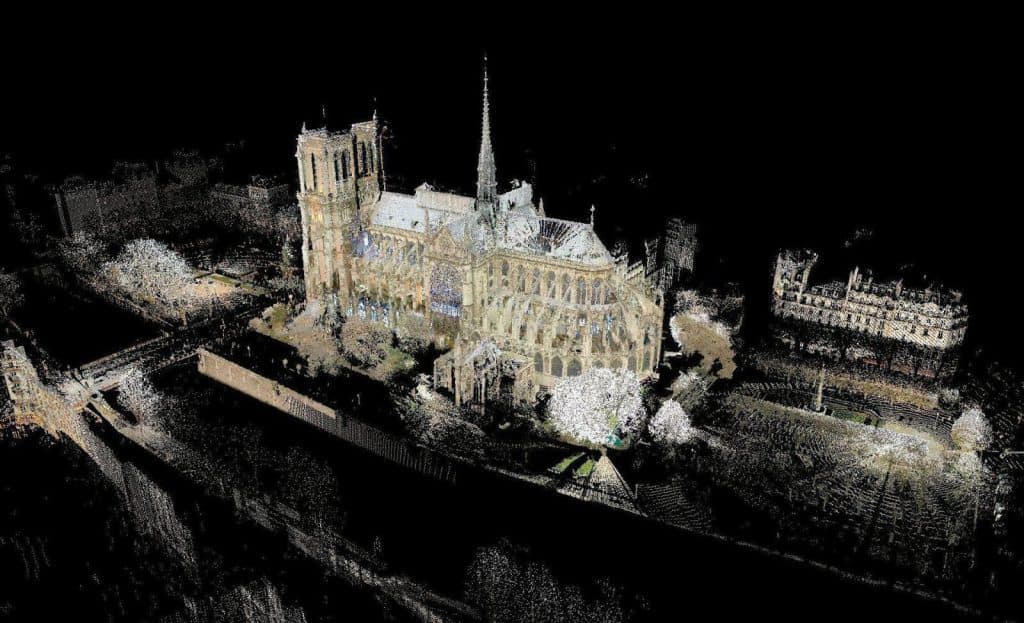

Keeping French President Emmanuel Macron’s promise to rebuild in five years the Notre-Dame of Paris exactly as it was before the April 15 fire could be possible in part thanks to Andrew Tallon, a professor of art history at Vassar College in New York State. Together with a group of colleagues, he carried out a three-dimensional laser scan of the famous cathedral in 2015 with a Leica ScanStation C10.

Tallon and his team spent five days working on and around the roof of the Gothic structure, placing a camera tripod in 50 different points and collecting over a billion images that, when merged, create a detailed digital map of Notre-Dame, according to the web site of Vassar College.

Furthermore, by combining 3D scans with high-resolution panoramic photos made by Tallon and his colleagues, it is possible to combine digital images with real ones to achieve a precise and detailed view not only of the structure, but also of the materials and construction techniques used. Tallon would later in 2018.

Michael Davis, professor of art history and chair of architectural studies at Mount Holyoke College of Massachusetts, confirmed the importance of this digital record for reconstruction work on the cathedral, according to an interview in U.S. trade magazine Engineering News-Record (ENR).

«Laser scanning can measure places and surfaces with tremendous accuracy that you could never hope to get to in person, such as the curvature of a flying buttress», said Davis, who is also a former colleague of Tallon’s. «I think the laser scanning offers a really useful document of the state of the structure».

John Russo, president of the U.S. Institute of Building Documentation, said the 3D scans will cut restoration time.

«Having laser scans [of Notre-Dame] is critical in shortening the reconstruction time frame», Russo, who is also president and chief executive of Architectural Resource Consultants, told ENR. «If you don't have that data, where do you go? You are going back to the hand drawings that may not be and those that are going to be two dimensional and not as much information. As far as answering questions and shortcutting the timeline on doing repair work, 3D scans are going to shave an incredible amount of time off».

However, the availability of 3D scans certainly does not eliminate the problems of reconstruction. The central theme during both the design and construction phase will be how closely to stick to the old structure and old construction techniques. The use of materials is also a crucial topic. English architects faced the same questions in 1984 when they were forced to rebuild the York Minster, which was also hit by a violent fire. Authorities chose to rebuild the church on the basis of its original structure, but also opted for innovative materials and systems, adding for example a sophisticated anti-fire system that protected it from future risks.

The same questions arise today with Notre-Dame, yet are even more complex because the Paris cathedral was built at different times, from the 12th to the 19th centuries, when its central spire (now destroyed) was added in a restoration.

Notre-Dame: from its origins to the present

Notre-Dame was built on sacred ground. Julius Caesar built there a temple dedicated to Jupiter in 52 B.C. to celebrate the surrender of Vercingetorix, the vanquished Gallic chieftain. In 1160, the Bishop of Paris, Maurice de Sully, started the construction of a large cathedral, starting from the demolition of the two existing churches, one dedicated to Saint Stephen and the other to the Virgin Mary. The building was completed in 1250. But it was not, in fact, finished.

Even under the Renaissance, from the 15th to the 18th Century, the cathedral underwent several modifications and was the focus of one of Louis XIV’s largest renovations.

Then came the French Revolution. The church was seized and made public property, transformed into the Temple of Reason. After the Revolution and with the rise to power of Napoleon Bonaparte, Notre-Dame was returned to the Catholic Church and the first mass was celebrated on April 18, 1802. Restoration and repairs continued throughout the 19th and 20th centuries until the fire on April 15.

The goal of rebuilding the church in keeping with the original structure is therefore all about respecting the historic complexity of modifications made over the centuries.

A competition for the Notre-Dame of the future

It is not yet clear what sort of Notre-Dame will rise from the ashes. Although President Macron has pledged to rebuild the cathedral in five years, and France’s leading businessmen have come forward with substantial donations, the architectural questions remain unanswered. French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe has launched an international architectural competition for the reconstruction of the collapsed spire, leaving it up to the world’s leading firms to envision designs that either rebuild the 19th-Century spire designed by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, or propose innovative solutions that reflect our present times.

Whatever the winning design will be, the detailed and almost unwitting work carried out in 2015 by the team of U.S. scholars will help create the Notre-Dame of the future thanks to a detailed map of one of the most visited buildings in the world.