What

do workmen talk about on their lunch break, sitting on a steel beam at

the top of a skyscraper? It is both an intimate moment and a collective

history, captured together by a photographer’s click. On one hand we see

the men’s faces, full of fatigue and satisfaction; on the other, the

epic story where they play a leading role: the construction of the

Rockefeller Center, one of the symbols of New York City and of America’s

rebirth after the Great Depression. In 1932, on September 19 to be

exact, Charles Clyde Ebbets (the most likely author of a photograph that

still hides a few mysteries) snapped the “Lunch atop a Skyscraper” that

immortalizes the workmen during their break and created an image that

is hard for anyone to forget.

It is this same magic that envelops the oil well fire fighter Paul “Red”

Adair, soaked in crude oil as he struggles to put out a blaze in

Kuwait’s wells with dynamite, photographed by maestro Sebastião Salgado.

It is 1991, and this photograph becomes a poster for the first Gulf War

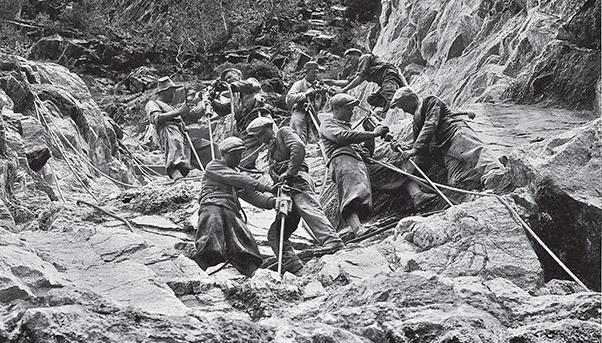

just as it was coming to a close. There are other photographs by

Salgado that depict work in a completely different way, not as a vehicle

for development – as a form of desperation, where the poorest people on

the planet struggle in a form of modern slavery, like the half-naked

men he photographed covered in mud in the gold mines of Sierra Pelada in

Brazil, where they toil in inhuman conditions seeking their fortune.

Thanks to the contribution of masters like these, photography has become a tool to narrate the evolution of professional know-how and the achievements of the human race.

Be they snapshots in black and white, posed portraits, or stolen images

of men as they climb sheer cliff walls, their strength lies precisely

in their ability to represent the immediacy of a moment, but also of the

absolute importance of the labors of mankind.

This representation of man also shows the importance of his

work, as well as the passage of time, the social and historical context,

and economic development. There are many photographers who

through their work became eyewitnesses to the Industrial Revolution. And

there are many that captured the golden age of infrastructure, when

pioneers set out to build works that would become universal symbols.

The first images of railways and railways stations spring to mind,

photographed in the 1800s by Edouard-Denis Baldus, or the images of

London’s Crystal Palace by Philip Henry Delamotte, or Delmaet and

Durandelle’s snaps capturing the most important moments of the

construction of the Eiffel Tower. Or the work of Gabriele Basilico, one

of the most well-known photographers of urban landscapes in the world.

His reportages from Milan, Shanghai, Istanbul, Silicon Valley, Rio de

Janeiro and Beirut are slices of life that bear witness to the story of

today’s urban agglomerations.

All of these experiences offer yet more proof of how man’s challenge to

realize epic infrastructure works has always captured the imagination of

the world’s great photographers, because stealing those images means

immortalizing an historic moment and telling the story of a world that

is destined to change.

Cyclopica, a photographic voyage

From the shots by British photographer John Myers of crumbling abandoned factories in the U.K. to Sweden’s Mårten Lange and his portraits that tell the tale of the solitude of today’s white collar employees, photography is capable of capturing the soul of a moment forever and then letting us relive it each time we stop to look.

This is the idea behind “Cyclopica,” the photography

exhibition organized by Salini Impregilo from May 1 to June 3 at Milan’s

Triennale. The show will recount moments lived by people in distant

lands and their epic adventures, and the unique experience of working

with hundreds of other people to build a large infrastructure project. The

men who opened a gap in the American continent to build the Panama

Canal, or the ones who brought electricity to Italy, contributing to the

country’s industrialization, thanks to the dams built by Edison in the

remotest towns in the Alps (immortalized by director Ermanno Olmi), or

dug tunnels burrowing hundreds of metres into the Earth show us how

they work. And with their work they create a Cyclops, or those

infrastructure giants that have helped entire populations grow.

It is through the relationship of man and the Cyclops – or between dwarf

and giant, but also between wits and strength – that over 2,000

infrastructure projects come to life through Salini Impreglio’s history

of over a century.

This relationship has been captured in over 1.2 million

images and 600 videos, conserved in the Salini Impregilo archives, from

photographers that the group relied on to convey its desire to talk

about its evolution from its origins 110 years ago to the present.

It was Antonio Paoletti and Guglielmo Chiolini who at the start of the

1900s were the first to preserve a record of life on a building site,

highlighting ambivalence about the difference between the enormity of

the structures and the human dimension – while still keeping man in the

foreground. Armin Linke, Moreno Maggi, Edoardo Montaina and Filippo

Vinardi took the same approach through the years right up to the most

recent works.

Today these images are being shared with the public in a selection that

takes the visitor on a voyage in time and space, through different

historic epochs and to faraway countries.