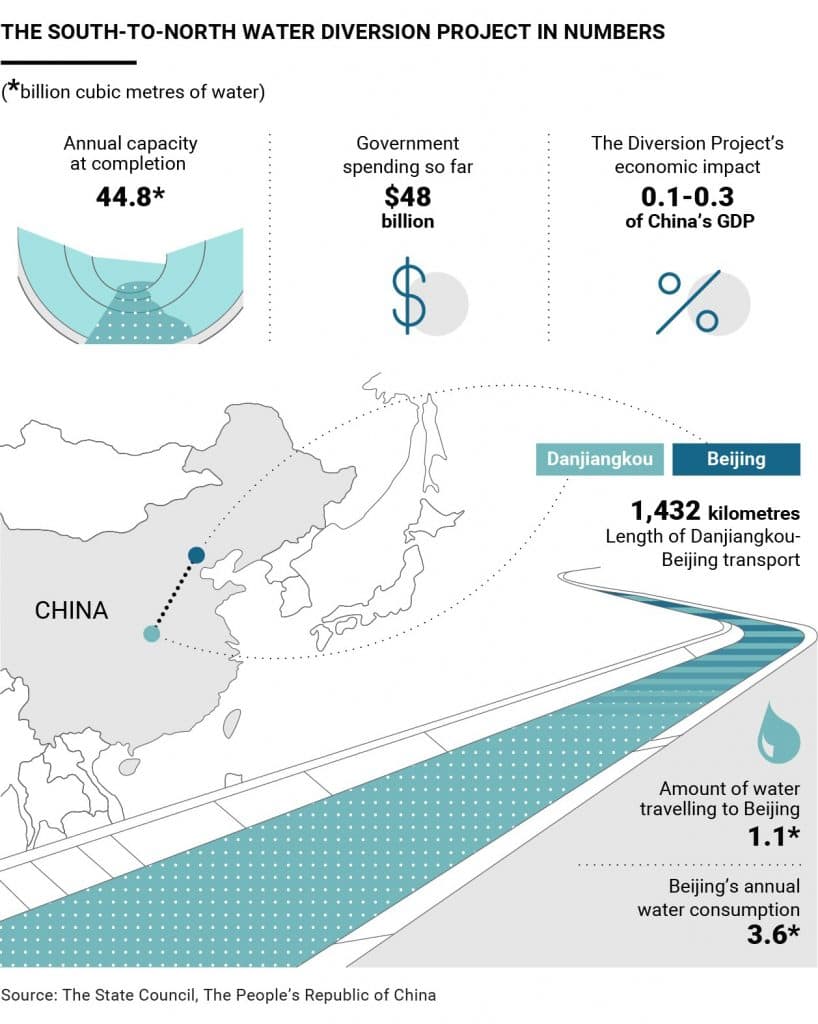

It is one of the most ambitious water management projects ever attempted: a series of canals, pipelines and tunnels transporting 44.8 billion cubic metres of water for over 1,000 kilometres. It is China’s solution to solve the drought problem plaguing its northern cities, starting with Beijing.

Hence, the South-to-North Water Diversion Project: to create a veritable water transport “highway” linking the country’s four largest rivers in the South (the Yangtze, Yellow River, Huaihe and Haihe) to the regions of the North. The project will be finished in 2050 and will cost $48 billion, more than double the initial budget forecasted and more than the $37 billion spent on the famous Three Gorges dam, according to the State Council of the People’s Republic of China and various media reports.

Part of the project has already been completed, and is a strategic solution protecting Beijing from the risk of a water shortage.

Water for Beijing

It did not rain in Beijing this past winter from 23 October to 13 March. The longest drought in the recent history of China’s capital city would have put a huge strain on the city’s water resources if it had not been for the water diversion network. The water comes from the Danjiangkou reservoir, near the former city of Junzhou, and makes a two-week trip covering 1,432 kilometers (about the same distance between London and Milan) until it reaches Beijing’s water treatment plants.

This network from Danjiangkou supplies two-thirds of Beijing’s tap water and a third of the total supply to the city. But Beijing is not the only one in need of water. Four-fifths of China’s water supply is in the south, where about half of the population lives. In the regions to the north, 11 provinces have less than 1,000 cubic meters of water available per person each year, which is the internationally accepted definition of water stress. Eight other provinces have only half that amount.

It is also an economic issue: the driest regions are home to the country’s five most important industrial areas that account for 45% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). In fact, once it will be completed, the water diversion network could boost China’s GDP by 0.1% to 0.3% each year. This figure alone can explain why the state is making such a huge investment to build what has been called the largest and most expensive infrastructure work in the world.

The project’s impact

The South-to-North Water Diversion Project is so complex that the government created a completely new company to develop it. The idea is to connect the four main rivers through a network of pipelines, canals and tunnels, to create an overall system where water can be sent along different routes.

One of these, the Eastern Route, opened in 2013, brings water to the province of Shandong, mainly from the Yellow River. To have an idea of its vastness, the diversion from the city of Yangzhou that brings water to the Weishan mountains in Shandong is 1,155 kilometres long and needs 23 pumping stations to keep water flowing along.

The water supply is significant, even though the Eastern Route has had a high cost on the regions it passes through. More than 380,000 people have been moved, as well as numerous industries that risked polluting the waters.

A project with a long history

The first person to envision a network capable of transporting water across the country was Mao Zedong. The former leader talked about the idea for the first time in 1952, saying it was important to bring water to the cities of Beijing and Tianjin and especially to the northern provinces that needed it the most, such as Hebei, Henan and Shandong.

“The South has plenty of water, the north much less. If possible, the north should borrow a little,” he was once quoted as saying.

Fifty years later, on August 23, 2002, the project was approved, with work starting the following year.

China struggles with its water problem

The South-to-North Water Diversion Project is an awe-inspiring endeavour. But it is not enough on its own to handle China’s increasing water consumption. Beijing by itself consumes 3.6 billion cubic metres of water each year. The city’s supply reaches only 2.1 billion, and the missing 1.1 billion comes from the south via the water diversion scheme. In short, the huge infrastructure effort under way is barely enough to meet today’s needs, never mind tomorrow’s. In fact, the Chinese government is forecasting that by 2020 Beijing will need four billion cubic metres of water. The same is true for the country’s north, where – according to the government – consumption will reach 200 billion cubic metres by 2050. Only one-eighth of this demand will be met by the network still under construction.

The numbers speak for themselves: not even the world’s largest infrastructure project can quench the thirst of the large cities of the North. And China will have to figure out a new plan. Soon.