What will become of the New Silk Road, the grandiose “One Belt, One Road” infrastructure project that was supposed to quickly and efficiently connect the Far East with Europe, along the same route traveled by Marco Polo almost 800 years ago?

China has pledged major investments to build an intermodal transport network connecting China, Mongolia, Russia, Central Asia, Pakistan, India, Eastern Europe to Venice and from there to London. The project’s future is not completely clear, and depends on the impact of Covid-19.

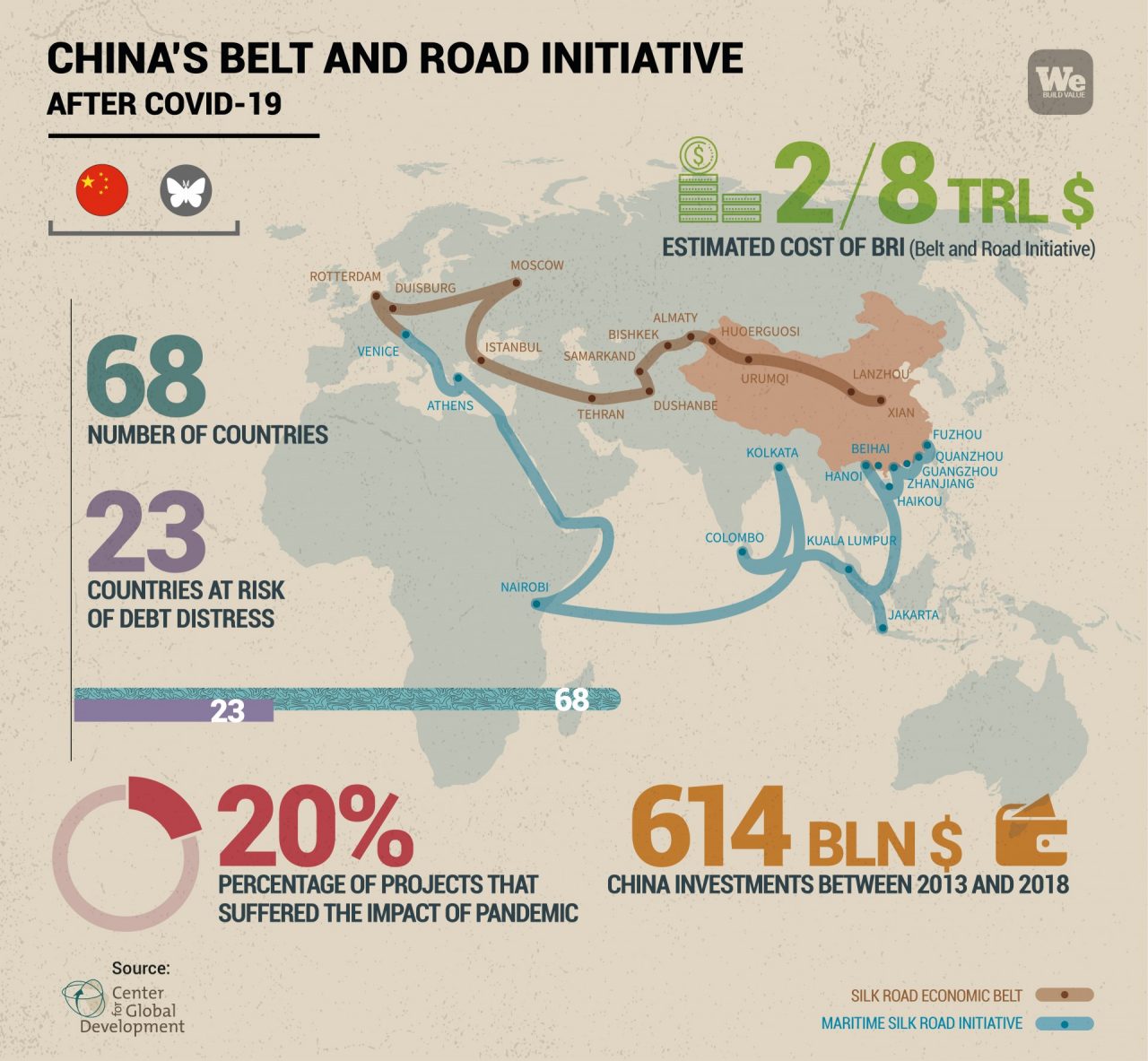

The spread of the pandemic, and the consequent closure of national borders, has forced the construction on projects to grind to a halt more than once. The cost — initially estimated at $1 trillion – was already seen increasing. Moody’s has estimated in a 2018 report the total outlay will reach between $2 trillion and $8 trillion.

International analysts are now convinced that the Belt and Road Initiative is no longer among the Chinese government’s top priorities. It is focused on post-Covid recovery, as indicated in the guidelines for a new five-year investment plan that will be announced in March 2021.

China Belt and Road Initiative: a major project in search of revamp

The first to launch the New Silk Road was Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, when he announced the Belt and Road Initiative that would create roads, railways, ports, and intermodal hubs, to facilitate the exchange of people and goods between Asia and Europe.

China invested more economic resources than any other country in the plan, at least until the outbreak of the pandemic. Between 2013 and 2018, Beijing has poured $614 billion into the project, 38% of which was allocated to the energy sector, 27% to transport, 10% to real estate. Over half of the resources have been allocated to Asia, 23% to Africa and 13% to the Middle East.

One sign that commitment was on the wane because of the pandemic — not only from China, but also from other countries involved—comes from China Railway, engaged in the construction of rail lines throughout the continent.

“Internationally, the global spread of Covid-19 has brought certain challenges to the overseas production and operation of Chinese construction enterprises… The [value] of new contracting projects from 59 countries along the Belt and Road decreased by 5.2% year on year to $60.3 bn,” according to China Railway’s 2020 Interim Report.

The risk of a slowdown for this ambitious investment plan was also confirmed last summer by Wang Xiaolong, director-general of the ministry’s International Economic Affairs Department, who admitted that 20% of the projects envisaged by the Belt and Road have suffered the impact of the pandemic. The perspective, shared by many, is that the project has become — at least in this point in history — too dispersive compared more immediate needs. The new five-year investment plan that will be launched by China in 2021 will be focused on the more urgent investment priorities necessary to support post-pandemic economic recovery.

China's 14th five-year plan

March is the target date chosen to present China’s 14th Five-Year Growth Plan to the world. The government started holding a series of meetings and analyses during the first weeks of October 2020 to prepare a long-term project that takes into account an immediate response to the Covid crisis.

According to many experts, including Wang Tao, chief economist at UBS Investment Bank in China, the plan will aim for lower and more flexible GDP growth than in previous years, therefore probably around 5% per year (from 6.5% in the previous plan).

According to initial analysis, the new plan will not change China’s strategy on infrastructure investment, which it continues to consider one of the most effective tools to boost the economy. Rather, it will redirect the same investments towards technology, environment and self-reliance goals that will be able to deliver concrete benefits in the short term.

Instead of focusing on the Belt and Road Initiative, one of the pillars of the new plan will be the evolution of the Greater Bay Area, the rich region that includes some of the largest Chinese cities, from Shenzhen to Hong Kong, and that will soon be entirely connected with high-speed trains.

This policy was outlined at the Central Economic Work Conference, the traditional meeting attended by the Chinese president with top government officials dedicated to economic strategies to be pursued in the coming year. At the event held on December 16, the priority emerged to provide effective responses to the pandemic and the changed international context and therefore major projects that boost domestic demand.

Leadership outlined another priority at the conference, which Covid-19 has highlighted not only in China but among all the most advanced economies, and which naturally concerns the strategic infrastructure sector. The pandemic has shown just how important it is for states to be independent, autonomous, and safe. Major infrastructure plays a primary role in guaranteeing these outcomes.