With just a few words of his inaugural address, U.S. President Joe Biden helped re-establish water infrastructure and construction and maintenance of America’s dams as a priority: “Ensuring clean, safe drinking water is a right in all communities – rural to urban, rich and poor – investing in the repair of water pipelines and sewer systems, replacement of lead service pipes, upgrade of treatment plants, and integration of efficiency and water quality monitoring technologies. This includes protecting our watersheds and clean water infrastructure from man-made and natural disasters by conserving and restoring wetlands and developing green infrastructure and natural solutions,” he said.

Although the Biden plan does not specifically mention the construction of new dams or hydroelectric systems, it has received a virtual seal of approval from public and private operators of a disgruntled sector. Under recent administrations, this industry has seen little concrete action taken on its behalf, and not because other sectors were simply higher on the priority list. One of the most critical factors inhibiting action is reconciling federal programs and funding with the projects and investments overseen by individual states.

It is not uncommon for state governors to have to cut projects that may have already secured 75-80% of their funding from the federal government, simply because their hands are tied at the state level (due in large part to constituents’ resistance to raising local taxes). This means that federal funds were often directed elsewhere.

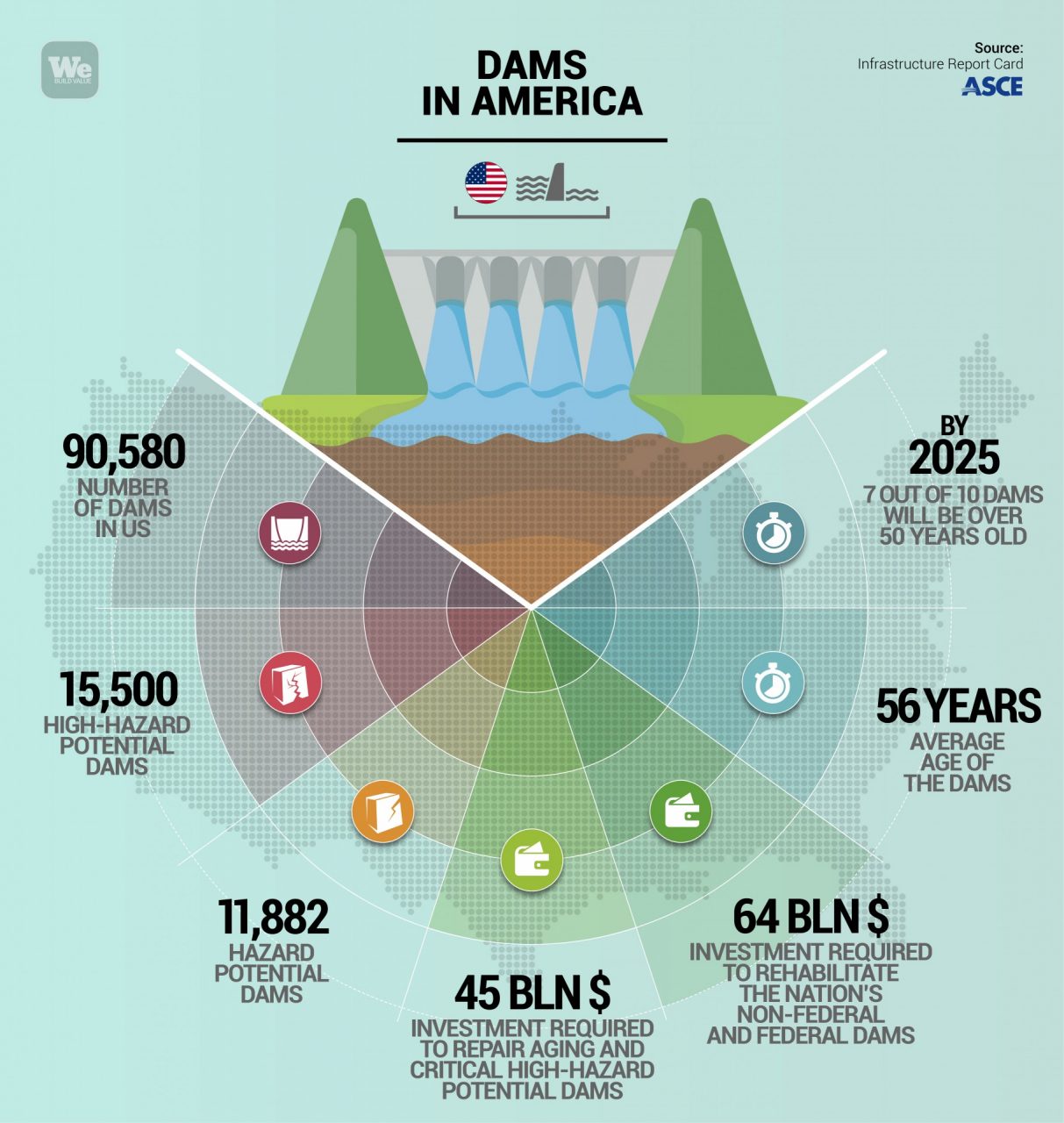

Water infrastructure is among the most vulnerable sectors on the country’s urgency map. According to the National Inventory of Dams (NID), a database run by the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), there are 91,457 dams in the United States. Their average age is 57. More than 8,000 of these are over 90 years old, and 17% have been classified as high-hazard potential. One estimate, released in 2017 by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), indicates that $45 billion (€37 billion) will be needed just to repair and secure the most neglected sites.

Biden’s pledge for clean and safe energy

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) is among the various government agencies that have a say on dams. More than 2,700 U.S. dams–3% of the total–serve a hydropower system. In his first round of executive orders, President Biden appointed Richard Glick to head FERC with the express purpose of ensuring safe, reliable, and cost-effective power in the years ahead.

“This is an important moment to make significant progress in the transition to a clean energy future,” Glick said on Twitter. Glick, who comes from the private utility sector, has experience at Iberdrola and PacifiCorp, among others. Glick has also served as general counsel for the Democratic Party on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

As a first move, FERC announced that it was investigating how to better ensure that companies owning dams have sufficient finances to properly maintain them. This was an initial response to the interconnected May 2020 collapses of Edenville Dam and Sanford Dam in Michigan. This event prompted flashbacks to three years ago in California, where the lesion of the Oroville dam’s emergency spillway was at risk of releasing a 32-foot (10 metre) wall of water on three counties north of San Francisco. Swift evacuation of 188,000 people and the securing of the facility by the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) prevented a catastrophe.

List of dams at high risk made public

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers follows the military hierarchy, and looks to the President of the United States as Commander in Chief. This body holds a central role in the design, construction, and maintenance of America’s dams. On January 25, four days after Biden took office, the USACE granted public access to a previously classified map of dams and floods. The document had always been limited to emergency management authorities and federal agencies, under a non-disclosure agreement.

In 1972, Congress granted USACE all compiling and managing responsibilities for the National Inventory of Dams (NID). The USACE is considered the highest authority on the subject.

Of the 91,457 dams, about 63% are privately owned, 20% by local governments, and only about 4.1% are federally owned. Another 4.2% are controlled by “public utility” and 7.4% by individual state agencies. Some 1,366 remaining dams have an “indeterminate” ownership status.

Dams safeguarding America from floods

Approximately 20% of the dams in the national inventory exist primarily for flood control. The USACE estimates that $5 billion (€4.1 billion) in damages have been avoided to date from dams and flood control levees in Central Valley, California, and, for example, in the Tennessee Valley.

In the Midwest and the South, levee system construction became more widespread after implementation of the Flood Control Act of 1936 by the USACE. This change encouraged urban and agricultural development in the fertile floodplains along the Mississippi River and in the wetlands of Florida. Over the years, local governments and taxpayers set their sights on land reclamation. Such is the case in the famed Everglades in South Florida, where major projects have gotten underway, including the Caloosahatchee C-43 West Basin Storage Reservoir (WBSR), overseen by Lane Construction (a subsidiary of Webuild Group) and aimed at redeveloping marshlands and containing wastewater.

Constructing a reservoir in the Caloosahatchee Estuary, with an earthen dam with a 16.3-mile (26.2-kilometre) perimeter and a 2.8-mile (4.8-kilometre) septum separating the two reservoirs, will keep contaminated water from nearby residential and agricultural areas under control during rainy periods. During drier periods, the reservoir will provide adequate water supply for maintaining optimal salinity levels.

Betting on America’s dams for agricultural development

The creation of an American dam system aimed at urban agricultural, energy, and irrigation development began in 1902 with Congress’ passage of the Reclamation Act. This led to the founding of the Bureau of Reclamation and the construction of major dams for irrigation and hydroelectric production. One example is Hoover Dam, completed in 1936 and still one of the most visited feats of engineering in the United States. Hoover Dam was designed to produce hydroelectric power, tame flooding along the Colorado River between Nevada and Arizona, and provide drinking water and irrigation to millions of people through the formation of Lake Mead. Lake Mead is the United States’ largest reservoir by volume and the main water source for the city of Las Vegas.

Although substantial and well-managed, Hoover Dam has been affected by climate change and the ever-increasing water demands of the gambling and entertainment mecca. In 2014, then, Lake Mead was outfitted with Intake 3, a hydraulic tunnel 200 feet (6 metres) deep, built by Webuild to combat Colorado’s drought and to restore the lake’s water supply to a sustainable level.

Divergent readings of ecological impact led to a mid-1990s freezing of new U.S. plans for large dams. This has heightened the risk that many of these infrastructures are outdated or do not comply with current legislative and regulatory standards. There is also considerable disparity at the state and federal levels on regulations of all kinds: safety, maintenance, management, inspection, and emergency plans all vary from state to state. All this has favored dismantling the existing structures. According to the American Rivers Association, which safeguards natural waterways, 1,722 dams were removed nationwide between 1912 and 2019, and an additional 69 in 2020.

The Biden administration has pledged to take action on this issue, ensuring a green, clean and sustainable future through better water infrastructure.