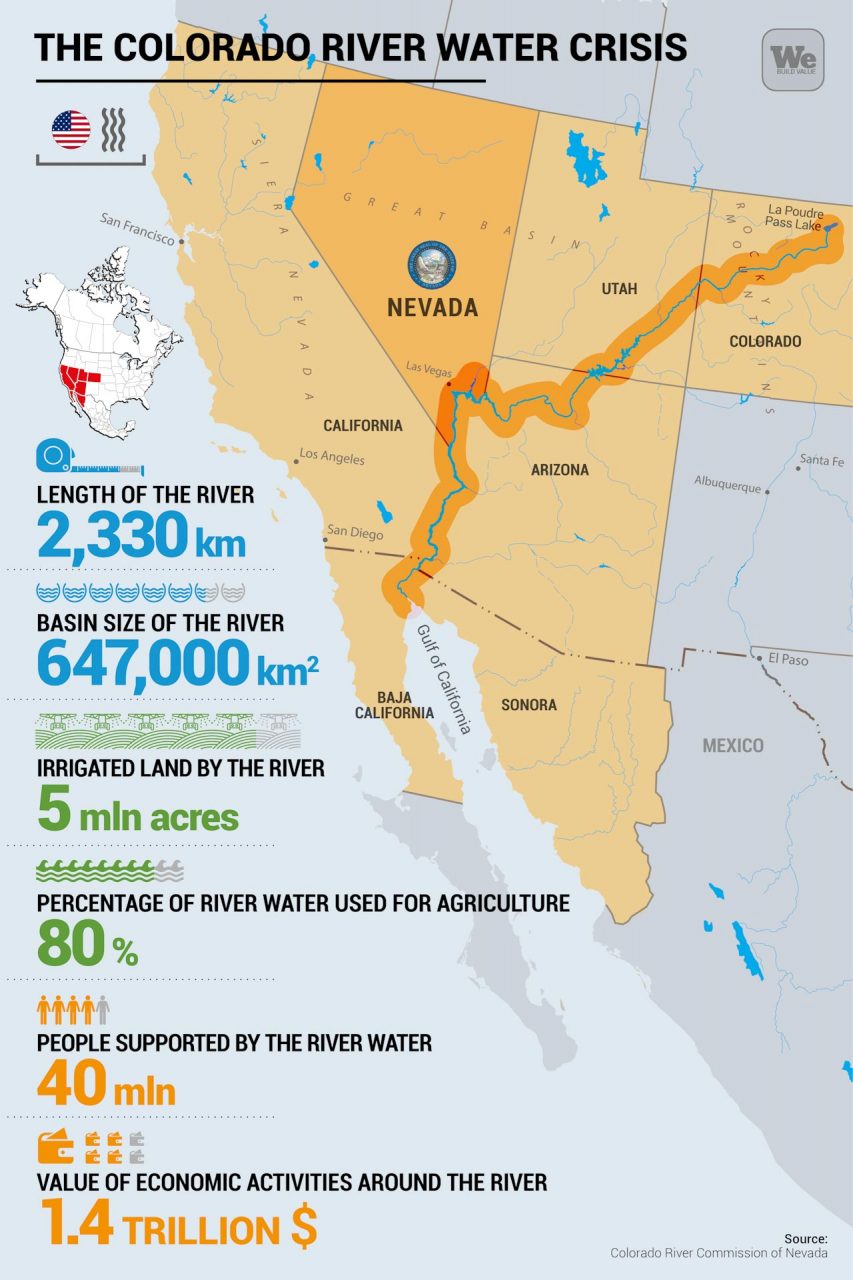

There are three numbers, lit up like alarming red flags, on the screen of the U.S. Drought Monitor. Every Thursday, it updates U.S. governing bodies on drought levels across the country, with a focus on western states and water emergencies on major rivers. The Colorado River is one of them, and its numbers are massive: it provides drinking water to 40 million people, irrigates 5.5 million acres of farmland and farms, and supports $1.4 trillion in economic activity.

The Colorado River originates in the state of the same name at an elevation of 3,100 meters (10,000 feet) in the heart of the Rocky Mountains and travels 1,450 miles (2,330 km) through seven states before plunging into the Gulf of California just across the border with Mexico, where it has been arriving for years already dried up. The river has a hard time reaching the sea. Today it is ranked as America’s most endangered river due to rising temperatures and drought caused by climate change, combined with outdated river management and over-allocation of limited water resources. Its flow is at an all-time low.

Colorado River drought emergency: the contingency plan

The drought emergency has landed on the table of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. On June 14, Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton told the Committee during a hearing that “more than 70% of the western United States is experiencing severe or extreme drought conditions.” In much of the Southwest, California, and parts of the Pacific Northwest and Missouri River Basin, the drought footprint “is likely to intensify over the summer, with severe to exceptional droughts in those regions,” Commissioner Calimlim Touton said.

The Colorado Basin is in its 23rd year of historic drought. Both Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the two largest reservoirs in the United States, “are at historically low levels with a combined storage capacity of 28%,” reported Calimlim, who provided estimates for the coming months. Lake Powell will end the calendar year with reduced water elevation at 3,522 feet (22% of its full capacity), while Lake Mead, which is the largest reservoir in the United States and provides nearly 90% of the drinking water to Nevada, will touch 1,039.92 feet (27% full).

Third Intake to take water from Lake Mead

The drought, however, did not take the Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) by surprise, which has been installing pumping systems over the years. The first intake pipe at Lake Mead was built in 1971, 35 years after the reservoir was created with the construction of the Hoover Dam. In 2000 a second pipe was built going even deeper into the lake. An ongoing historic drought has reduced flows in the Colorado River. This in turn reduced the amount of water in Lake Mead to a point where lake levels could shrink until the original two intake valves were left uncovered.

With Las Vegas relying on Lake Mead for 90% of its water needs, “it was not a gamble the Southern Nevada Water Authority was willing to take,” reports the National Park Service on its website, which adds, “A plan unlike any other ever conducted anywhere in the world was devised: the creation of a ‘third straw.’ The design of the intake pipe is unique; instead of the pipe coming from above the surface and down into the water, SNWA built an underground tunnel that comes from below the lake and channels water from the bottom of the lake, similar to a drain on a bathtub.”

The project, dubbed “Intake 3,” or “Third Straw,” was contracted to the Webuild Group. It set new records due to its hydrogeological complexities, such as the water pressure bearing down on the technicians driving the TBMs (the mechanical cutters) that reached as high as 15 bars, five times higher than the average pressure for this kind of excavation.

The drilling required complex maneuvers, such as blasting rock and listening to seismic reflections to create a geological map so as not to proceed blindly into the lake bottom. The work was done, the National Park Service concludes, with “a drilling rig of epic proportions, with over 1,500 tons and a length of two football fields.”

As expected, as the lake levels gradually lowered, the first straw, or Intake 1, surfaced in spring 2022 and its upper grid is visible today. The third straw, completed in 2017, has thus become the indispensable key to providing water to more than two million Las Vegas residents and its 40 million annual visitors.

Protecting the Colorado River from drought

Without hyperbole and confirming the soundness of the investments made early on, SNWA General Manager John Entsminger reported at the same June 14 Senate Committee hearing that the Colorado River’s situation “is objectively bleak, it is not in my view unsolvable. There is little we can do to improve the Colorado River’s hydrology. The solution to this problem—and by solution I don’t mean fully restoring reservoir levels but rather avoiding potentially catastrophic conditions—is a degree of demand management previously considered unattainable.”

Enstminger said that about “80% of Colorado River water is used for agriculture, and 80% of that 80% is used for forage crops such as alfalfa, which comes primarily for livestock.” The way forward, therefore, cannot be limited to trying to “stop farmers from farming, but rather to make sure that they carefully consider crop selection and can make the necessary investments to optimize irrigation efficiency.”

The federal government declared a shortage on the Colorado River last year for the first time, cutting water deliveries to Arizona, Nevada and Mexico.

“Agricultural production in the western U.S. is not replaceable; it is a vital strategic resource for America’s food security, for the ecosystem and rural communities, and for drought resilience itself,” Patrick O’ Toole, president of the Family Farm Alliance, retorted during Senate hearings.

The need “to do more, all together, to save more water” was raised by Camille Calimlim during the Senate hearings. “No amount of funding can make up for the severe rainfall shortages we are experiencing this year throughout the American West. We will experience inevitable reductions in agricultural water supplies and hydropower production,” she concluded, however, referring to another drought-related problem.

If the water level of Lake Mead, now at 1,045 feet above sea level, continues to fall, eventually the Hoover Dam will no longer be able to provide hydropower. Below the level of 895 feet, water no longer flows through the dam to supply California, Arizona and Mexico, a level that would make the lake what the media called a “dead pool.”

Entsminger, on the strength of Intake 3, reassured Nevada citizens that the installed system was effective. He urged them to do more, however, especially downstream of the lake. “I urge every user of the Colorado River to follow our lead and do everything possible to preserve what is left of the Southwest’s lifeblood. The future depends on it.”