Twelve billion euros versus 4.7 billion euros. The gap is huge, and yet this is the difference between what Infrastructure Minister Enrico Giovannini has calculated the government would need to spend to solve Italy’s water problem and the funds that are currently available. Some of the available funds come from the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), and the rest are drawn from dozens of different funding sources.

It’s the summer of an historic drought, with the flow of the Po River at 60% below average and Lake Maggiore at 24%; crops all over Italy parched and corn withering on the stalk. There was 46% less rainfall from January to May than the average of the last 30 years (in the North, the deficit is 60%).

Agricultural lobby Coldiretti quantified the losses to their agriculture business at €3 billion euros and the REF Ricerche Study Center calculated that the industry at large would lose 5 billion in sales for every percentage point of water rationing. Italy is in the midst of a perfect storm, with the shortage of financial funds only getting worse.

June had the second-hottest average temperatures ever recorded in Europe, with a temperature 1.6 degrees Celsius (about 3 degrees Fahrenheit) above average. (This number also shot up due to extreme temperatures recorded in Spain, France and Italy, where the highest temperature was nearly 3 degrees Celsius, or about 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit, above average). The fight for sufficient funding for water reclamation has begun again. The fight already began years ago and has already made many mistakes: the “National Plan of Infrastructural Interventions and for the Safety of the Water Sector,” for example, was initially allocated only €100 million for ten years in 2017, or €1 billion. It’s only been through the goodwill of various ministers and other stakeholders that other financial sources have been added, and the total allocation has grown to €2.02 billion, or an additional €1 billion, to be used from 2018 to 2033.

Water resource control: too many agencies and divided responsibilities

The battle, as seen from the initial figures, is far from over. Meanwhile, the situation should be improving at the institutional level: as Minister Giovannini mentioned in a parliamentary hearing on July 5, the compartmentalisation of stakeholders and managing bodies is discouraging. In fact, the Ministry of Infrastructure is not only responsible for water resource management activities, but also for coordinating with the Ministry of Ecological Transition on environmental regulation and energy policy, with the Ministry of Agriculture for irrigation planning, with the sector authority ARERA (which was only recently vested with responsibility for water resources) for economic regulation, with seven river basin district authorities, and, of course, with the regions as grantors of water service management as well as with the concessionaires themselves, which are often totally inadequate in terms of organisation, competence and speed of execution.

Finally, there is the issue of relief with funding from the National Solidarity Fund for Damaged Farmers.

Are there enough resources? Not a chance, with only €13 million currently available. The budget is blatantly insufficient.

Water: a cultural battle

Even leaving aside regulatory shortcomings, Italy, one of the countries most affected by drought, is far behind in the cultural battle for proper water resource use. Suffice it to say that only 11% of rainwater is collected when, according to research, up to 30% could be collected and reused. Then there is the famous estimate of 40% of drinking water lost along the peninsula’s aqueducts. An NRRP-financed project takes direct aim at this deficit: in fact, the plan to modernise the network with €900 million in public spending is already underway.

The wastewater issue is another prominent one: it mostly comes out of clean-enough sewage treatment plants, yet gets thrown away, into rivers or the sea, without proper evaluation of its possible reuse. According to the interactive map of the Water Information System for Europe, where data are published on each country’s progress toward wastewater treatment goals in addition to protection of sensitive water systems, sludge use and greenhouse gas emissions from the sector, in the 27 European Union (EU) member states, an average of 90% of urban wastewater is collected. But in Italy, we collect less than a third of that. Meanwhile, paradoxically, people continue to use potable water even in agriculture, perhaps simply because it costs less than connecting to a sewage treatment plant even in the same area. It should be kept in mind that Italian agriculture uses 51% of all available water compared to the European average of 40%.

Finding solutions to the water emergency

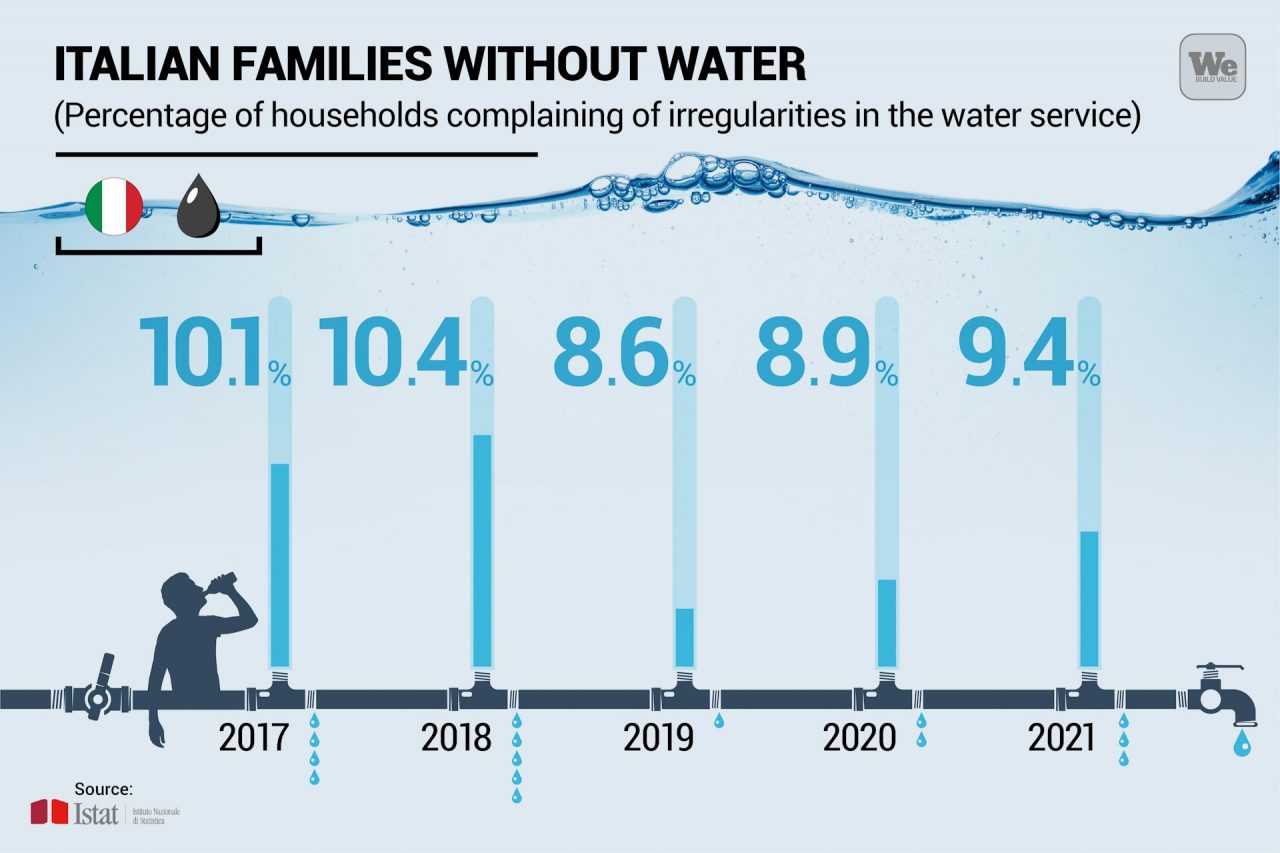

As always in hard times, ill-concealed tensions are emerging, even though Istat confirms that one billion cubic meters (35.3 billion cubic feet) of water out of the 33 of national consumption is missing. Water shortages appear to be a symbol of human selfishness re-emerging (an apt term).

When the idea of helping the Po River by resorting to the waters of Lake Garda was suggested, the Lake Garda community immediately protested. The Valle d’Aosta Region also refused requests for help. The region’s governor, Erik Lavévaz, in response to the governor of neighboring Piedmont, Alberto Cirio, said: “We, too, have serious critical issues.”

At the European level, things are even worse: the Ministry of Agriculture asked Brussels at the end of June to increase advance payments of EU agricultural funds for the most affected sectors, but the response was vague.

In short, this summer of drought, against the backdrop of war at Europe’s borders that is already causing a frightening food crisis, is also the moment of truth for a long series of historically unresolved issues bubbling up to the surface. But there are also industrial stories of progress that could point toward a better future.

In the Chiomonte construction site, the main Italian construction site on the Turin-Lyon railway line, the Webuild Group has developed a project that involves the collection of groundwater from the streams inside the Maddalena Tunnel.

These natural waters will be diverted to irrigate 12 hectares of vineyards in the area. The case of Chiomonte project confirms that an increasing number of companies are engaged in circular economy operations and contribute to the rationalization of water use.

It’s the same idea behind Webuild’s proposal to build a desalination park that can respond effectively to the Italian water emergency (not coincidentally, in the wake of similar operations launched by Middle Eastern countries). These are major investments, of course, but the costs of prolonging the emergency would be far greater.