The story of Italian migration is also the story of modern Australia. Thousands of workers left their homeland for a faraway country to rebuild their lives and ended up building – along with their own futures – the impressive infrastructure that would become the backbone of a rich and innovative continent.

Bridges, roads, dams, hydroelectric plants, railways: many of Australia’s important infrastructure works built between the 1960s and 1970s bear the signature of the thousands of Italians who had crossed the globe to escape post-World War II poverty.

It is a story of a tradition handed down from father to son from past to present, to the engineers and technicians who in 2022 are building Australia’s most modern works.

The story starts with the Sydney Opera House, the construction of which began in 1959, and reaches all the way to the Snowy Mountains Nature Park, about a five-hour drive from the capital, where today Italian engineers are part of the team that is building Snowy 2.0, one of the country’s largest hydroelectric plants.

It is a journey through time and space, through the old and the new Australia, a country built in part thanks to the commitment and talent of Italians who have come from afar.

Italians in Australia: a postwar opportunity

In the post-World War II era, Italy was a poor and defeated country. Italians were a people overwhelmed by economic hardship and in search of a new land where they could work and grow.

And so between 1947 and 1976 at least 300,000 Italian migrants landed on Australian shores. About one-fifth of the total arrived under the Italian Assisted Migration Scheme of 1951, a reception plan created by the Australian and Italian governments at the time.

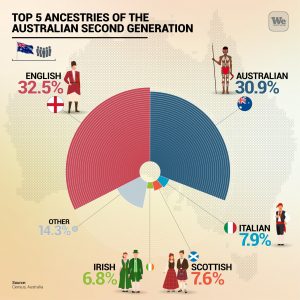

By 1971, there were 290,000 people born in Italy registered with the country’s Census, a number destined to decline over the years to 163,000 today, while at least 1.1 million people claimed to have an Italian ancestor in their family tree.

In the 1970s, Italy was the second country of origin for Australian inhabitants after England, a natural hub of attraction that would give hundreds of thousands of people a shot at redemption.

According to Australian Census data, almost all of the Italian migrants who moved to Australia between the 1950s and 1970s were employed in the construction of major infrastructure works, confirming the role they played in the construction sector where Italians had advanced experience and technical skills.

Highway 1 and the others, on Australia's major infrastructure construction sites

Working at the Highway 1 construction site was like being part of history. When the National Route Numbering System, or the unification of Australia’s road system, was created in 1955, Highway 1 was at the heart of an ambitious federal mobility project. Even today the highway, nearly 14,500 kilometres (9,000 miles) long, circumnavigates the country, touching all the state capitals apart from Canberra. A large number of Italian workers, mainly from the South, have worked on its construction sites, as well as on the sites of the West Gate Bridge, the bridge spanning Melbourne’s Yarra River. This bridge was the scene of the worst workplace accident in Australian history. On October 15, 1970, a span of the bridge under construction collapsed, killing 35 workers.

Aside from the sad case of the West Gate Bridge, the history of Australian construction sites, like the Melbourne metro system, is a history of economic development that has helped make the country one of the places with the best quality of life in the world.

From the 1970s to the present, the challenge of Italians in Snowy's worksites

Fabrizio Lazzarin is 47 years old and has been working in Australia since 2018. “I arrived in Sydney after having spent six years on construction sites in Africa,” he says, “and right away I appreciated the beauty of this city.”

Lazzarin is an engineer at Webuild, selected from an early stage to work on the Snowy 2.0 project and its implementation. This maxi project involves the construction of a pumped-storage plant and nine hydroelectric plants capable of increasing the facility’s clean energy generating capacity by a further 2,000 MW of clean energy, reaching the needs of 3 million homes for more than a week.

“After the first year,” he continues, “I was joined here by my family, my wife and my two children, ages 7 and 13, and we are rebuilding our lives here.”

Fabrizio spends five days of the week at the base camp in Cooma, a five-hour drive from Sydney, an outpost to Snowy’s construction site. Here he serves as Deputy Project Director and Technical Director, so he is in charge of checking the progress and quality of the work, and also overseeing the technical aspects. “There are about 50 Italians on site, and of course we represent a cohesive group, although we have bonded with everyone,” he says.

Webuild is part of the Future Generation joint venture, and from the beginning the shared goal has been to pool skills and talent.

“We miss Italy,” Lazzarin admits, “but this is a country with wonderful nature, a public administration that works very well, and beautiful cities. We are far away, but we are part of a great project, modern and sustainable, and this makes us proud.”

The same pride that has marked the life story of the thousands of Italians who have left their signature and sweat on Australia’s great works.