Beneath the streets of London, hidden below the foundations of the city’s Victorian buildings and far from the noise of heavy traffic, moles are digging a deep web of underground tunnels. This time, however, the new tunnel network is not adding to London’s already extensive Tube. Its purpose is to light up the UK capital, and turn it on like never before.

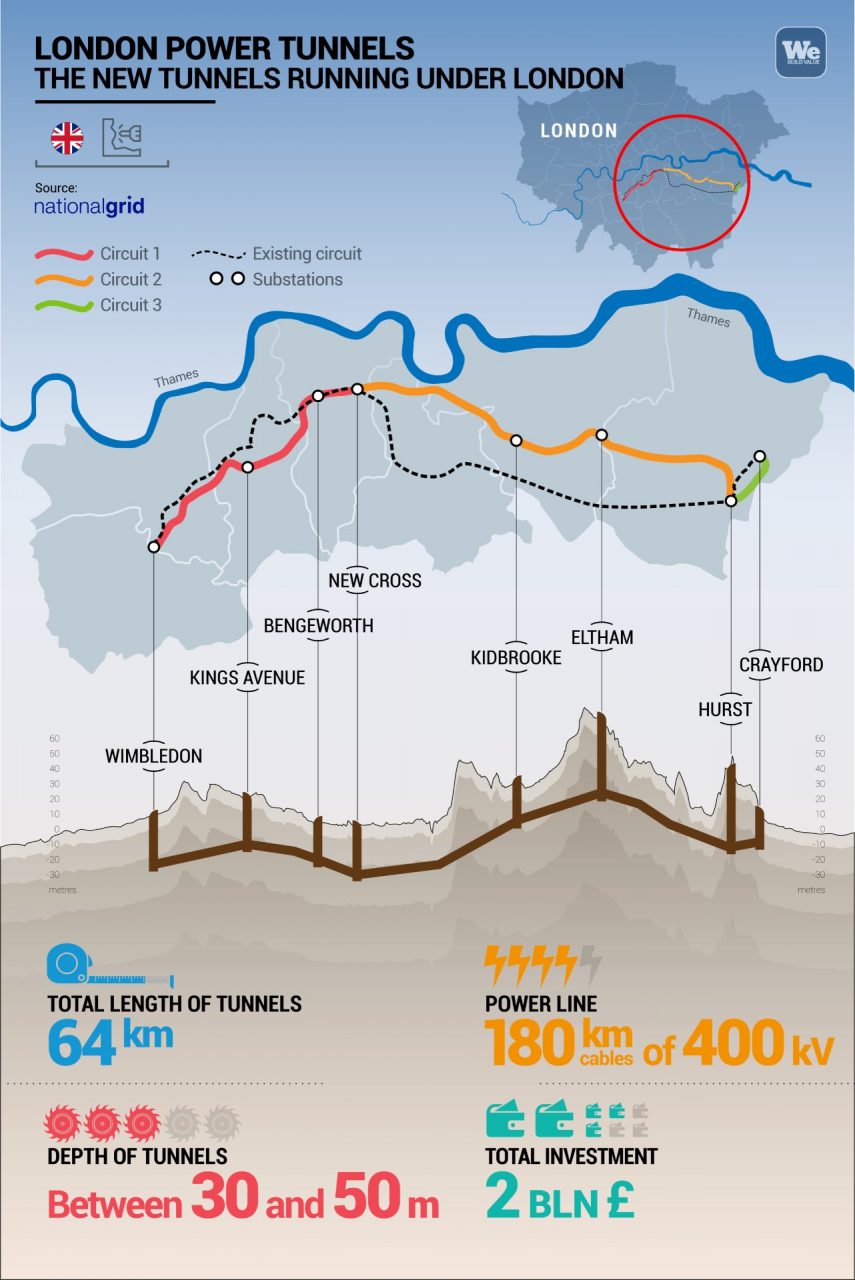

The London Power Tunnels project being carried out by the National Grid Plc plans to rebuild a major portion of the city’s power grid, making the cables that run just inches from the streets a thing of the past. It will create a deep underground highway dedicated exclusively to the grid, with tunnels between 30 and 50 metres (98 to 164 feet) below ground that will make the network viable for another 120 years. This is the first major investment in the capital’s electric transmission system since the 1960s. An unprecedented project, funded with a total investment of £2 billion. Its ambitious goal is to meet the capital’s growing energy demand in a modern and sustainable way.

London PowerTunnels: the project

From time to time, strolling through the busy streets of London, you can spot the open construction sites of the London Power Tunnels. They are chasms in the ground that plunge deep beneath the surface, where a small microcosm of machinery and workers toil. Fourteen years of work to dig over 64 kilometres (39 miles) of tunnels which will house 180 kilometres (111 miles) of 400kv cables. This is enough to light up the city and more generally bring electricity to the homes and businesses that need it. Due to its complexity, the project was divided into two phases: the first phase, completed in 2018, involved the construction of the first 32 kilometres (19.8 miles) of tunnels and focused on the North London area, with the construction of two substations and the first network of tunnels between Hackney in the city’s east, and Willesden in the North. In addition, another west-south link was created between Kensal Green and Wimbledon. The works carried out in the first phase of the project alone now meet 20% of the English capital’s electricity needs.

The second phase began in 2020, and is still ongoing. It involves extending the completed tunnels by another 32.5 kilometres (20 miles). These super-wide tunnels have a diameter of 3 metres (9.8 feet) and run from Wimbledon to Crayford and, are designed to be big enough to allow future upgrades and maintenance work to be carried out inside.

Londoners visit the energy tunnels

From the outset, the London administration wanted the residents to share and take part in the project. This was considered necessary in part because of the impact of the construction sites on people’s daily lives, and in part to explain to residents the importance of a project that will help profoundly modernise London’s energy supply.

In this sense, students have been the main target. In the areas most affected by the excavations, primary and secondary school pupils have been taken for tours inside the tunnels. For example, about 30,000 secondary school students visited the excavations in phase one of the project, while more than 50,000 primary school children took part in online lectures and meetings explaining the project itself and also the importance of sustainable energy consumption, according to National Grid.

London perpetually hungry for energy

London is one of the world’s most vital and wealthy capital cities. This metropolitan area of nearly 10 million inhabitants is in perpetual motion, and covers an area so vast that it exceeds 1,500 square kilometres (606 square miles). Above all, it is an economic engine producing one-fifth of the UK’s GDP and boasting a GDP per capita almost double the European average.

All of this requires energy, and the infrastructure for transporting electricity becomes strategic to ensure that London’s engine does not grind to a halt. Just a month ago, the BBC was reported to have been preparing for a possible risk of electricity shortages unable to meet London’s demand. On that occasion, Mayor Sadiq Khan called for a greater effort from the energy multi-utilities in charge of the capital’s energy supply.

Earlier this year, according to the Greater London Authority, the absence of electricity could slow down as many as 50 major real estate development projects in the metropolis, now scheduled for completion between 2023 and 2043. These include social housing projects, and then rent-controlled housing for less affluent families.

A slowdown that the British capital cannot afford and that it now hopes to avert with the new tunnel network that will soon run under the city.